A subset of the Hard History project

Call Us! (by Sunday, April 19)

Special Episode

It’s time for our first call-in show! We know things are chaotic for you and every other educator right now. We feel it too, so this seems like the perfect time to talk. Pick up the phone and dial 888-59-STORY (888-597-8679). Our lines are open until Sunday night, April 19. Teaching hard history is even harder right now, so let’s talk about resources you can use if you’re teaching virtually. Ask us your questions; tell us your stories. And let us know how you’re doing.

Whether you work with elementary, middle or high school students or whether you teach social studies or English language arts, the coming months are a good time to plan how you can bring accurate, foundational content about enslavement into your lessons. Tell us how you’ve been introducing your students to enslavement. What have you learned? What can we do to help? And we’ll try to have you on the show next week.

P.S. If you like, you can also email us at lfjpodcasts@splcenter.org.

Print this Page

Would you like to print the images on this page?

Subscribe for automatic downloads using:

Apple Podcasts | Google Music | Spotify | RSS | Help

Transcript

Meredith McCoy: Hey, Hasan.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Hey, Meredith. It’s good to hear from you. How’re you holding up over there with all that’s going on?

Meredith McCoy: You know, we’re week one into teaching in our new term. We’re on trimesters here at Carleton. You know, a new group of students. They seem to be coping alright. We’re just… we’re going to get through it together. How’s stuff going for you?

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Pretty good. We’re on semesters, so we sort of came back from an extended Spring Break.

Meredith McCoy: Mmm.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: And I’ve really been amazed at how well the students have adjusted.

Meredith McCoy: Oh, that’s good.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: It is good! But I’m not so much worried about them, Meredith, as I am about me! ‘Cause fourth-grade math is about to kill me!

Meredith McCoy: Oh no!

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: But you know, with a little practice, I boost my confidence. And I’ll get through this with my girls. It too shall pass, and we will get past it.

Meredith McCoy: Oh, I’m sending you good vibes. Good luck.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: I appreciate it. I appreciate it. I need all of it, all of it. So hey, what do you say? You want to get started?

Meredith McCoy: Yeah, yeah. Let’s do it. Let me head upstairs.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Alright, I’ll find a quiet corner, too.

Okay, close the door for me, Layla? And tell your mother to hang up the phone, stop talking so loud?

Daughter: What phone?

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Tell her to stop talking so loud.

Meredith McCoy: Y’all better cut that.

He’s going to get in trouble if you leave that in the audio.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: “Tell your mother, I said…”

Meredith McCoy: Good luck.

I’m Meredith McCoy

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: And I’m Hasan Kwame Jeffries. And this is Teaching Hard History: American Slavery.

Meredith McCoy: A special series from Teaching Tolerance, a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Hey Meredith, do you mind if we turn off the theme song now.

Meredith McCoy: No, that’s okay. I really do like it, though.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: This is such a different time. And this isn’t a normal episode.

Meredith McCoy: Absolutely.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: With all of the changes that each of us are facing right now, we’ve decided to shift gears with our podcast too. It’s time to come together. So we were thinking: what if we do a call-in show? We could talk to some of our listeners—talk to you—to find out how you’re doing, and to ask how you’re using the framework to teach about slavery, and what we could actually do to help you out.

Meredith McCoy: So we had our team set up a number where you can leave a voicemail for us. You can call, tell us what subject you teach and what you want to talk about. Because we want to hear from you – the teachers and educators in our audience.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Exactly. We want you to share your perspectives, your experiences, your ideas, and the challenges that you are facing as you endeavor to teach hard history accurately and effectively. So if you can spare a moment, all you have to do is pick up the phone and dial 1-888-59-STORY. That’s 888-597-8679.

Meredith McCoy: So in the next episode, we’ll share your messages, address your questions, and have some of you on for an in-person conversation with us. Hasan, what was that number again?

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: That’s 1-888-59-STORY. And here’s our Executive Producer Kate Shuster calling in, so you can hear what that sounds like:

Kate Shuster: Hey, Meredith. Hey, Hasan. It’s Kate Shuster, calling from Montgomery, Alabama. Everything is tough right now. But I’m doing okay, and I’m glad that y’all are too. I’m spending quarantine doing chores I never usually would, like cleaning the windows. And, that’s given me a better view of my cats trying to hunt lizards outside.

I am super excited that you’re doing a call-in show. I think that our listeners are really going to want to share their stories and ask questions. And I am thrilled to hear what they have to say! I feel like educators are doing extraordinary things in these extraordinary times. I’m just real thankful that you’re here to support them. We’re educators. We’re used to challenges. We’re going to get through this together and come out better on the other side. That’s all I have to say, and you know how to get in touch with me. Good luck!

Meredith McCoy: Thanks, Kate. That’s so true. Look, we know that everyone is overwhelmed right now. As teachers, we are struggling to figure out how to teach online, how our students can access lessons, how to teach kids who might be overwhelmed with additional home responsibilities. And that’s even if our students have adequate access to technology and resources at home, let alone how we can support students with unstable housing right now. So in the call-in episode we will also address distance-teaching challenges and specific resources for teaching hard history that you can plug-in to the new digital formats we’re all adjusting to right now.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Like so many things, the history of American slavery might seem like the last thing that anyone wants to think about. But slavery’s long-lasting legacy helps explain the painful reality that African Americans and Native Nations are being hit disproportionately hard by this pandemic. And as we’ve heard from a lot of educators, this is also a time for thinking about what comes next. And whether you work with elementary, middle or high school students—whether you teach Social Studies or English Language Arts—the coming months are also a time for planning and reflection on how to bring new and interesting content into our lessons.

Meredith McCoy: So as you’re looking back over the last year, what new topics related to the history of American slavery have you tried to teach in your classes? And how did your students respond? Where have you found ways to incorporate Indigeneous enslavement into your existing lessons and learning goals? Are there any concerns that are standing in the way of trying something out? And have you found successful strategies for engaging parents and other teachers in this content?

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: How are you introducing your students to systemic concepts like labor and land theft, or racism? If you teach younger children in elementary school, what ways have you tried to introduce them to the history of slavery?

Whatever you’re experiencing, you can be sure you’re not alone. And we are here to wrestle with these challenges together and learn from each other.

Meredith McCoy: So pick up the phone and give us a call. Most importantly, let us know how you’re doing. And then also tell us how teaching hard history has been going in your classes. Feel free to tell us a story about something that’s happened during a lesson. What are you hoping to incorporate in the future? And if you’ve encountered problems that you’d like some help thinking about, let us know! Tell us about needs that you see or resources that would be helpful for you. And if you’re excited and proud of things you’ve tried with your students, tell us about those, too. And Hasan, how do they do that again?

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Just give us a call at 1-888-59-STORY. You can find that number in the episode description. Or, if you’re tech-savvy, you can record a voice memo on your smartphone and email us a message at lfjpodcasts@splcenter.org. However, you want to reach out is fine by us. The important thing is that you get in touch. We genuinely want to hear from you.

We will be taking calls and emails throughout the week. So be sure to contact us by the end of the day on Sunday, April 19th.

Meredith McCoy: But you don’t have to wait. Go ahead and pick up the phone and call us now. And with that, shall we wrap this up?

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Let’s do it.

Teaching Hard History: American Slavery is a podcast from Teaching Tolerance—a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center—helping teachers and schools prepare their students to be active participants in a diverse democracy. This special series provides a detailed look at how to teach important aspects of the history of American slavery. You can find us online at learningforjustice.org.

Meredith McCoy: Our production team—Shea Shackelford, Russell Gragg, Barrett Golding, Gabriel Smith and Kate Shuster—deeply, deeply appreciate your patience as we work out the technical kinks of recording this podcast now that everyone is sheltering in place.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: And to all of you listening, we want to say thank you for being a part of this with us. Along with everyone at Teaching Tolerance, we are thinking about you during this difficult time. And we are so excited to talk with you in our upcoming episode.

Meredith McCoy: Stay safe y’all.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: I’m Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries—Associate Professor of History at the Ohio State University.

Meredith McCoy: And I’m Dr. Meredith McCoy—Assistant Professor of American Studies and History at Carleton College.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries and Meredith McCoy: And we’re your hosts for Teaching Hard History: American Slavery.

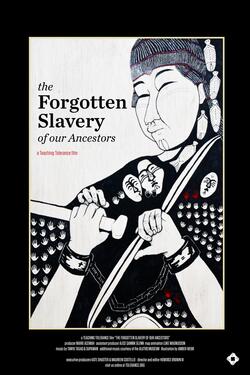

Inseparable Separations: Slavery and Indian Removal

Episode 13, Season 2

Indian Removal was a brutal and complicated effort that textbooks often simplify. It is also inseparably related to slavery. Enslavers seeking profit drove demand for Indigenous lands, displacing hundreds of thousands of Indigenous people. Some of these Indigenous people participated in chattel slavery. Focusing on the Chickasaw and Choctaw nations, this episode pulls the lens back to show how Removal and enslavement must be taught together. This story must be told if we're going to understand the full hard history of American enslavement.

Print this Page

Would you like to print the images on this page?

Earn professional development credit for this episode!

Fill out a short form featuring an episode-specific question to receive a certificate. Click here!

Please note that because Learning for Justice is not a credit-granting agency, we encourage you to check with your administration to determine if your participation will count toward continuing education requirements.

Subscribe for automatic downloads using:

Apple Podcasts | Google Music | Spotify | RSS | Help

Transcript

Meredith McCoy: Here at Teaching Hard History, we know that our classrooms are in a state of a rapid and unforeseen change. We know that for many this is a time of confusion, apprehension, and uncertainty. And yet, we also know that some parts of life seem to keep moving. Our students are still looking to us for learning in whatever form that learning might be taking place. We want to continue to support you as best we can, and we'll continue to provide these episodes so that you can have resources that might be helpful to you, especially as you pivot to online and distance learning. Bear with us as we work out the logistics of producing these episodes while we and our guests are increasingly isolated, and we will continue to provide these episodes for you and your students. Now more than ever is the time to turn to our professional learning communities and support each other. I and the rest of the Teaching Hard History team are sending out to all of you best wishes for health and well-being.

Today, we're taking on a particularly challenging topic in our coverage of the hard history of America slavery, indigenous enslavement of African and African-descended peoples. This is a fraught subject, one that can seem incredibly complicated and dangerous. Native people are already so often stereotyped as violent, and this seems to add fodder to an inaccurate and incredibly damaging narrative. And yet, as scholar Tiya Miles reminds us in a recent interview with Teaching Tolerance magazine, Native American history can and should be treated with the same degree of nuance with which we now treat US history.

This topic is not one we enter into lightly. We must tell these stories carefully with an eye to the economic and social pressures native people faced as settlers increasingly encroached upon and forcibly evicted native people from their homelands. As we tell this story, Miles offers us guidance, which I'll quote at length. She says, "Teaching the history of indigenous enslavement of others is indeed a challenging task, especially given concerns that some educators may feel about preexisting stereotypes of Native Americans as savage and about exposing historically oppressed and marginalized groups to further scrutiny. However, no population is exempt from the complexities of being human or the complexities of organizing societies that conceive and commit atrocities. To deny the ability of any people to do terrible things, to harm others, or to fail expressed ideals would be a denial of their membership in the human family."

These nuances are important to keep in mind as we think about how to teach not just the history of how settlers enslaved native people but also how native people enslaved others. We're talking about a relatively small number of native people in the 19th century who had the economic capital to hold others in bondage. This is a story that must be approached with nuance, specificity, and a lot of context. And it's a story that must be told if we're going to understand the full hard history of American enslavement.

I'm Meredith McCoy, and this is Teaching Hard History: American Slavery, a special series from Teaching Tolerance, a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center. This podcast provides a detailed look at how to teach important aspects of the history of American slavery. In each episode, we explore a different topic, walking you through historical concepts, raising questions for discussion, suggesting useful source material, and offering practical classroom exercises. In our second season, we're expanding our focus to better support elementary school educators, to spend more time with teachers who are doing this work in the classroom, and to understand the often hidden history of the enslavement of indigenous people in what is currently the United States. Talking with students about slavery can be emotional and complex. This podcast is a resource for navigating those challenges so teachers and students can develop a deeper understanding of the history and legacy of America slavery.

When we think about Indian removal, we might not always think about its relationship to the institution of slavery. But the United States is built both on its theft of indigenous lands and its exploitation of enslaved people for their labor. In this episode, we're going to talk with historian Nakia Parker about the impact of removal on the expansion of enslavement. Dr. Parker sheds light on the complicated context in which some indigenous people participated in enslavement. And throughout or conversation, she shares several helpful stories and resources that you can use with your students. I'm so glad you can join us.

Nakia, welcome to Teaching Hard History. We are so glad that you're here with us.

Nakia Parker: Thank you for the invitation.

Meredith McCoy: So today we're going to be talking about how indigenous people sometimes participated in the institution of chattel slavery. As we move into today's episode, what are some key things that you think teachers should prepare themselves to be able to discuss with their students?

Nakia Parker: I think that teachers should be prepared to discuss, first of all, how the arrival of Europeans, and invasion on native land, and colonialism affected indigenous captivity practices as well as how native nations became involved in the enslavement of African-Americans. And another major point to remember that teachers can pass on to their students is that Indian removal and slavery are not separate, unrelated events. They're intertwined. So the expansion of slavery in the Deep South does not happen without Indian removal.

Another thing that's important for teachers to remember is that native history during this time period, 19th century America Indian history, is very important to understanding the history of the US South, to understanding the expansion of slavery, and also important to teaching slavery in the 19th century and how it developed to our students. We have to include aspects of America Indian history like Indian removal.

Then, another important thing to remember is that historical actors often have to make hard choices. And systems of oppression often overlap one another, and we'll definitely see that in our discussion when we look at how native people handled Indian removal and how native slaveholders brought the institution westward to Indian territory as well as in our discussion of freed people's rights.

Meredith McCoy: I'm excited to talk with you about these things. Could you start just by telling our listeners a little bit about you, what you study, and how you came to be studying it?

Nakia Parker: Sure. Broadly, I'm a historian of 19th century African-American and American Indian history, US slavery, and also gender enslavery. But more specifically, I study the lives of enslaved and free people of African and Afro-native descent and the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations. I look at their lives during the removal period of the 1830s after the passage of the Indian Removal Act and follow their experiences into resettlement in Indian territory, what we now know as present day Oklahoma, during the 19th century.

So how I became interested in this research, I was an undergraduate at the State University of New York at Newpaltz. I took a class of the American Civil War and our final assignment was to do a research paper on any topic that we chose about the Civil War and I decided that I would write about American Indian participation and the conflict. I assumed that these two groups were likely comrades in struggles against white supremacy and oppression. I reasoned that most native people must have fought for the Union, certainly they had to be on the side of abolitionist and protected enslaved people and even helped them to get to freedom. And indeed I did find examples of protection and cooperation between native people and African-American people. I even found examples of native people who fought on the side of the Union. But image my surprised when my professor told me that there were some nations that did side with the Confederacy, in particular, five major nations who had homelands in the southeast. The Creek, the Cherokee, the Choctaw, the Chickasaw, and the Seminole all allied with the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Then, my shock deepened when my professor told me that some native people enslaved African-Americans and that the last general to surrender in the Civil War was a Cherokee general, Stan Watie. So this rattled me, really, to learn that some native people participated in the institution of chattel slavery. And by chattel slavery I mean people as property. People could be bought, sold, insured, willed. This was the institution of slavery in the United States. It certainly was a history that I didn't learn from my parents, I didn't learn at school, and certainly not in the dominant narrative, the dominant narrative in American popular memory, that there were some native people that participated in the institution.

Meredith McCoy: Given what you're describing, how did settler encroachment and other pressures for social change influence how indigenous people were thinking about enslavement?

Nakia Parker: Well, for a brief time after Europeans arrived and invaded native soil, some white colonizers enslaved native people, particularly women and children. So native people for a time worked alongside people of African descent in places like Virginia and South Carolina. African people and native peoples were enslaved together. They intermarried. They even rebelled against enslavement together. But by the mid 17th century, the dynamic start to change. Enslaved Africans become the preferred laborers, especially with the expansion of the transatlantic slave trade. Some European nations, like England, Spain, France, they desired to form alliances with native people, and it's not a good political strategy to enslave allies.

So some native societies, especially nations in the southeast, like the Chickasaw and Choctaw, they're keenly aware of these economics and social dynamics that are happening and these different dimensions of European settler societies and their slaveholding practices and they begin to participate in slave catching, first by trading native enemies to the British and French, and then later they become involved in capturing enslaved African-Americans when the enslavement of African-Americans becomes entrenched in colonial settler societies.

So by the late 18th, early 19th century, some native people in the southeast graduate from becoming slave catchers to actually enslaving African-Americans and people of African descent. They become wealthy sometimes by participating in the institution. But they see enslavement of African-Americans as a way to secure or maintain a semblance of political autonomy, of economic autonomy while also pursuing self-interested economic and political goals. They're trying to combat another form of oppression, which is settler colonialism.

Meredith McCoy: Teachers, particular teachers working the southeast, may have come across this term of the five tribes or the five civilized tribes in their curricular materials. Could you explain who that's referring to?

Nakia Parker: Yes, absolutely, because there are over 600 native nations in the United States, and we're referring to in particular five major nations that had ancestral homelands in the southeast that were removed westward. These nations are the Cherokee, the Creek, the Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole. Their homelands were originally east of the Mississippi in states such as North Carolina and Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Florida. Teachers may be familiar with the term the five civilized tribes, and that was a term used to describe these nations because these were five nations that particularly adopted certain white European and American norms, such as written constitutions, governing structures, written language, gender norms, Christianity, as well as, for some native people, the adoption of enslavement practices, enslaving African-Americans as well.

Meredith McCoy: So in your thinking about enslavement in these five nations, how does that adoption of chattel slavery compare with forms of captivity that these nations might've practiced prior to their interactions with Europeans?

Nakia Parker: Many native societies engaged in captivity practices for centuries prior to European invasion. But Indian captivity practices and slavery was not hereditary, it wasn't unchangeable, and it wasn't based on any notion of racial superiority. So what do I mean by that. In other words, you weren't born into slavery. You weren't considered a slave for life. Captivity didn't mean that slavery was passed on or captivity was passed on from mother to child or was transgenerational. And it wasn't justified by the argument that one group of people were racially inferior and therefore were meant to be in slavery. Instead, captivity generally was a byproduct of war. It was a possible outcome for enemies who were on the losing side of a war.

Captives were often involved in political negotiations, and they also could be adopted as kin or family members into a tribe or clan to replace deceased relatives. For the captives who were not adopted, they remained outside of kinship networks, a permanent outsider in a socially marginally place, but there were limits to their subjugation. But, these practices start to transform with European invasion on native soil. There's increasing trade, and then there's the introduction of the colonial practice of racialized chattel slavery. So again, what I mean by chattel slavery is people as moveable property. And that was an introduction, a colonialist introduction, and it dramatically reshapes and adds a different dimension to indigenous captivity practices.

So when I teach this topic to my students, especially the part about native people being engaged and selling other native people as slaves to Europeans, to the British, to the French, sometimes they express confusion of that or they'll echo a sentiment and they'll saw, "Well, that means Indian people sold their own people." And I hear similar sentiments when I talk about the transatlantic slave trade. And when students find that some African people participated in the transatlantic slave trade, they'll say something similar. It was Africans selling their own people. But what I highlight to them is that we can't categorize native or African people as one homogenous group with similar backgrounds, with similar aims, cultures, even languages. It's really colonialism that introduces the idea to lump all native people or all people of African descent into one group.

And I tell them when we talk about this time period in history and we discuss the different European powers who vied for supremacy on native land, for the most part, we don't say the Europeans. We specify. We say the British had these interests, the French had these interests, the Spanish did, the Dutch did, the Swedes did. We realize that they had different goals, different political structures and societies. The same thing applies to native people. The Cherokee, the Seneca, Mohawk, the Choctaw, the Shawnee, they all had different goals, different societies, even languages. And the same things applies to African nations as well, such as Ghana, and Mali, and Songhai. And they're searching to combat and adjust to new threats against their sovereignty as their own distinct society and as their own distinct nation. So that's something that we need to remember when we teach indigenous captivity practices and participation in the enslavement of African-Americans that I think will help us to teach this difficult narrative.

Meredith McCoy: That attention to the diversity of native nations is so critical. And I think teachers have two opportunities here. One is to really deeply engage with the concept of sovereignty, which is native nations' inherent right to self-governance. And the other opportunity is to have students looking at the treaty documents themselves. Because as they have students looking at treaties between, let's say, the Choctaw Nation and the US government, they're able to see that the federal government is making these very calculated decisions about how to interact with specific native nations on the basis of what those native nations are arguing for and also what the US government's interests are in those areas.

Nakia Parker: Yes, I completely agree.

Meredith McCoy: This is Teaching Hard History: American Slavery. Along with this podcast, you can find our new, first of its kind K-5 framework for teaching slavery to elementary students, including 20 age-appropriate essential knowledge sections, over 100 primary source texts, and six inquiry design models at tolerance.org/hardhistory. Again, here's Nakia Parker.

I think it is a useful classroom tool to take a comparative approach to removal and understand how different nations experienced removal distinctly from one another and in that way to illustrate that removal was a content-wide phenomena. Teachers could think about what removal was like for the Navajo Nation compared to the different bands of the Potawatomi Nation compared to nations in the southeast. And by looking at those difference and experience, over time, they're able to help students understand, again, the diversity of native nations and that even removal, something that we tend to be exposed to in textbooks as just something that was experienced by the Cherokee Nation was actually a much more common phenomena.

Nakia Parker: I agree with that.

Meredith McCoy: There's a much more common policy.

Nakia Parker: Yeah, that's an excellent point, Meredith. Like you said, we tend to center the idea and the story of removal on the Cherokee, so imply in the southeast, and we need to remember there were Midwestern, people in the Midwestern United States that were also removed, like you said, the Potawatomi, the Shawnee, the Delaware as well were removed. One big idea that I want our listeners to take away today if nothing else is that you cannot teach the expansion of slavery in the 19th century United States without teaching Indian removal. They are not separate events. They are intertwined. One does not happen without the other. And I think one of the great tools to use in the classroom that I've used with my students is maps to explain that.

So I take two maps side by side. I show them a map of where the homelands of southeaster Indian nations are as of 1830, and they can see it's mostly the South, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana. And then I show them a map next to it of by 1850 a map of the largest concentrations of populations of enslaved African-Americans in the United States, and I ask them what similarities do they see and it comes to them almost right away, that where the largest population of enslaved African-Americans are in the United States is in these same homelands, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina. So it's a potent way to show how the expansion of slavery and Indian removal are intertwined.

Then I explain to them that most enslaved African-Americans and native people experience multiple forced migrations in their lifetime. And to think about this that at the same the domestic slave trade is transporting over 1 million African-Americans from the upper to the lower South. This federal policy of Indian removal is expelling thousands of American Indians from their homelands in the southeast and in the Midwest of the United States. These two forced migrations expulsions are happening simultaneously. So most of the time, we focus on these processes as separate rather than intertwined events. But in reality, Indian removal not only forces native people westward but it also facilitates the expansion of slavery in the Deep South.

Meredith McCoy: So Nakia, I wonder if you could explain a little bit more this idea of allotment and what that means and how perhaps the counting of enslaved people was a factor in how allotment worked in relation to removal.

Nakia Parker: While Indian removal expands the growth of slavery in the South, it also expands slavery westward because indigenous people who enslaved African-Americans could bring enslaved people to their new home in Indian territory. So though although aspects of removal negotiations with the federal government differed, provisions concerning the institution of slavery received similar treatment in the five nations. I particularly researched the Choctaw and Chickasaw so that is mostly who I will refer to today.

But, treaties and policies created to enforce Indian removal really accommodated, even maintained the institution of chattel slavery. So for example, both the Choctaw and Chickasaw removal treaties allotted private reservations of lands to native individuals and heads of families in Mississippi and Alabama until they were ready to move westward. Then at that time when they were ready to remove, the person could sell their section of land, their allotment, for money and/or buy what the government referred to as portable property, which was simply just a euphemism for enslaved people, enslaved African-Americans.

But even though treaties acknowledged the existence of slavery, federal government agents still had to work out the logistics, the physical logistics of bringing in slave people on the removal trail. So for a time period, removal agents even questioned whether enslaved people should even receive rations on the trek westward. Because they said, "Well, if they're property and not people, why should they receive food? Why should they receive blankets? Why should they receive anything to drink?" Federal officials finally decided that enslaved individuals would receive the same amount of rations as native people who were forced westward.

In addition, we can see in sources that even can be pulled up online that federal Indian agents added columns to removal roles to include the number of enslaved people traveling with a group. Some Indian agents even suggested that identifying physical characteristics of enslaved people should be listed on the removal roles just in case an enslaved person decided to liberate themselves from enslavement. Then they could be easily recaptured if they took notations of physical characteristics. We don't see that in any of the roles presently, but it was a suggestion offered by a federal official. So even though the federal government dispossessed native people of land, they still took extra precautions to protect investments in human property.

But, Indian removal also aggravated class distinctions in some native nations as well. So for example, if you're a wealthy slaveholder, you would have access to more allotment of land. Because one of the things, for example, that the Chickasaw removal treaty dictated was that if you received allotments of land according to the number of people in your household, and that included enslaved people. So if you had 10, 15, 20 enslaved people, you would receive a larger allotment of land that you could sell and get more enslaved people to remove west.

Some slaveholders who were wealthy and therefore had access to these kind of resources sent their enslaved people westward first to begin the process of insettlement. The enslaved people arrived at Indian territory, started cultivating the land, starting rebuilding homes. And as they labored, these native enslavers returned to their lands east of the Mississippi and they brought their family members to their new homes in Indian territory. For example, in the Chickasaw Nation, two members of a prominent slaveholding family named the Loves, they removed in this manner. So Benjamin Love, for example, sent for his wife and his children after he sent his enslaved people to Indian territory to start resettling the land. Then he sent his family. Another member of the Love family entrusted his son, Overton ... This was Henry Love. He entrusted his son Overton to bring 25 individuals that he enslaved. It was 11 men and 14 women. He sent Overton westward with these enslaved people before he came with the rest of his family.

So with the aid of enslaved workers, some native slaveholders, particularly wealthy, could rebuild their homes. They could continue a plantation, comfortable lifestyle that they had acquired before the federal government took their land and forced to Indian territory. But imagine if you were not a slaveholder or if you only had one or two enslaved people, as the majority of people in southeastern Indian nations did not enslave people or had very few enslaved people, then the economic strain of removal was even more devastating.

But in addition, Indian removal also brings economic benefits to white settlers in nearby areas, such as the state of Arkansas. Arkansas is a pivotal state to consider when we teach the history of Indian removal. Normally, it's a state we don't think of. We usually focus on Georgia. We focus on Mississippi and Alabama. But all five nations of the southeast had to cross Arkansas to get to Indian territory. Fort Smith and Little Rock were pivotal places, particular Little Rock, as far as a supply depot for Indian removal.

So the commissary general who was tasked with overseeing the physical logistics of Indian removal actually wrote to removal agents in Arkansas. For one group, there was a group of a thousand Choctaws who were about to pass through the region, and so he instructs agents to tell the nearby settlers to not plant cotton, to plant corn and raise cattle because these would be the rations that Choctaw people would need for removal and then they could sell it to them for exorbitant rates. In fact, he said, "Tell them to raise corn and cattle. Hold out every proper inducement for them to raise both in quantities sufficient to meet the expected demand." So this directive to white Arkansas settlers to plant corn, to raise cattle instead of cotton really demonstrates the profitability of Indian removal for the old southwest.

And indeed, just five years after the first wave of Choctaw forced migration, which occurred in 1831, Arkansas becomes a state in 1836. So no doubt the process of Indian removal contributed to this developed. It not only freed up land for white settlement but also Arkansas becomes this supply depot to finance Indian removal.

Meredith McCoy: For teachers who might be joining us from Arkansas, this information that Nakia is sharing with us fits really well into Arkansas history standards, particular for seventh grade which features a standard that says, "Students should be able to analyze the impact of geography on settlement and movement patterns over time using geographic representations and a variety of primary and secondary sources." And they cite specifically something that they refer to as involuntary migration, which we would certainly argue includes removal.

Nakia Parker: Absolutely.

Meredith McCoy: For Arkansas students in high school, there's a standard that asks that students will be able to evaluate intended and unintended consequences of public policies, which specifically includes Indian removal. Nakia, all of the things that you're describing here reveal the extent of calculation and logistical planning on behalf of the settler state in this expulsion, as you say, of indigenous peoples from their homelands. How can we help teachers and students understand the visceral experience of the horror that really was being on the trail and being removed?

Nakia Parker: I think it's important that we talk about and uncover as much as we can the voices of enslaved people and native people who experienced removal. A good place to start is the WPA Slave Narratives and an extension of the WPA Slave Narratives, which is called the Indian-Pioneer Papers. It was also a part of the 1930's Works Progress Administration's narratives. They're online on the University of Oklahoma's website, their Western History Collections website. It contains thousands of interviews, but some of them discuss removal, what families remembered about removal or stories that were passed down. Two in particular stick in my memory. One is of a woman Sarah Harlan who was a Choctaw woman who was forced to remove to Indian territory with her family and enslaved people a little later time in the 1840s. So this is also good in teaching students that Indian removal was not just a short period of time. Sometimes this extended for decades for some native societies and communities.

Sarah Harlan is forced to remove to the west in 1840s and she recalled the grief that occurred when a five-year-old enslaved boy died during the journey to the west. He was playing with other enslaved children on one of the wagons. So Sarah Harlan was a wealthy Choctaw woman, a slaveholder, so she could remove with more resources. Enslaved people, slave children were playing on one of her wagons. The little boy slipped and fell and the wheels accident ran over him and crushed his chest. Sarah went to the closest town that she could to receive medical attention but it was too late for the enslaved boy. The doctor could do nothing to save him and the boy died that evening. So Sarah is recalling this in her memoirs decades later and she says she still remembers the crying and she remembered how the enslaved people traveling with her sang no more for many days. So that gives an example of the physical trauma and psychological trauma of removal.

Another example is runaway ads, also that we can find online in, for example, a historical newspaper database. Runaway ads during the time of removal always show how enslaved people resisted removal and how removal could tear apart their family. I've seen, for example, a runaway ad that was for two enslaved men who had liberated themselves and were caught in an Arkansas jail. The ad said that they were caught on the road leading to Little Rock, Arkansas in company with immigrating Choctaw Indians. So obviously these enslaved men tried to get into a group of native people, of Choctaw Indians that were removing. Perhaps there were other enslaved people in this group. Perhaps the group of Choctaw people decided that they would provided refuge for these enslaved men. We're not sure, but we know that they were caught with a group that was removing, expelled to Indian territory.

One of the men that was caught, Ben, claimed that his wife belonged to a Choctaw slaveholder that had already been expelled to Indian territory. So this provides an interesting example because it shows that Indian removal separated enslaved families. Perhaps some native slaveholders decided against taking all family members to the west. Maybe one ore more members were owned by a slaveholder who did not have to move to Indian territory. So Indian removal also devastated enslaved families as well. We usually think of the separation of enslaved families when we talk about the domestic slave trade. But these kind of incidents, and this trauma, and the severing of family ties also could happen during Indian removal, too.

Meredith McCoy: This is Teaching Hard History: American Slavery. We'll put a link to Sarah Harlan's story and the rest of the WPA Indian-Pioneer Papers in our notes for this episode at tolerance.org/podcast. While you're there, you should listen to our recent conversation with Cynthia Lynn Lyerly about using the WPA Slave Narratives in episode 11 of our current season. She gives some great advice about how to use these rich but complicated oral history collections with your students. Once again, here's my conversation with Dr. Nakia Parker.

Once the United States had removed these nations west, the nations had to reestablish norms for governance. And I wonder if you could speak to how they addressed enslavement in their new constitutions as they were trying to promote their own sovereignty and well-being.

Nakia Parker: Many nations established slave codes and codified the institution of slavery in their constitution. For example, the Cherokee, the Choctaw, and Chickasaw implement laws to maintain control over the enslaved people in their midst. One thing that they do is they set up what they call light horseman force, which really was similar to a police force and it was created to keep order, social order, in these nations. But also, it served as a way to control slavery and enslave people as well.

For example, one of the duties of the light horseman force in these nations was they needed to check the passes of enslaved people. So example, enslaved people had restrictions on mobility. If they wanted to travel anywhere off of their plantation or away from their enslaver, the enslaver had to write them a pass. And if they didn't have a pass, it would be assumed that the enslaved person was trying to liberate themselves, was trying to run away, and they would be punished accordingly.

So the light horseman force in Indian territory would check travel passes. They would return enslaved people who had run away back to their enslavers. They supervised public slave auctions, and they also punished anyone, either enslaved people or citizens of the nations, who transgressed these laws. Sometimes this involved physical punishment as well. They also passed laws in their constitution that said enslaved people couldn't read. They couldn't meet in large groups, in public places. They couldn't own a gun or a knife without their enslaver's permission. And years later, enslaved people still remember patrollers and these laws with fear and also with hatred.

But we also have to take into account the geopolitical environment that these nations are operating in, and in particular thinking about, for example, the Choctaw and Chickasaw who are surrounded by Texas to the south, a major slaveholding state, and then to the east they're bordered by Arkansas, another slaveholding state. Particularly in Texas, what we see is the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations are accused of being a place where enslaved people could run, and hide out, and find refuge. A lot of Texas slave holders would cross into Indian territory and try to either steal enslaved people that they claimed that were theirs or try to accuse Choctaw and Chickasaw citizens of harboring enslaved people.

So perhaps one of the reasons that these codes, particularly harsh codes, are passed in Indian territories is that Choctaw and Chickasaw political leaders are aware of this. They're aware of this assault on their sovereignty and autonomy and they're trying to protect it and show that we are not a place where enslaved people can necessarily hide out and find refuge. What you do see, too, is when white Texas slaveholders, some Arkansas white slave holders do cross into Indian territory, political leaders do express their concern to the federal government and demand protection and demand redress when white slaveholders do not respect native sovereignty. Sometimes it's listened to, but for the majority their calls go unheeded.

Meredith McCoy: For teachers who are teaching about removal, they might move from removal into thinking about the Civil War. And we tend to teach the Civil War as though the only parties are the Union and the Confederacy, but the reality is so much more complicated when we also think about how native nations were viewing the Civil War. So Nakia, how might teachers talk to their students about how native nations viewed and participated in the Civil War?

Nakia Parker: That's a great question. I think it's important to highlight to students that really there's a diversity of experiences with native people who experienced the Civil War. Actually, it's at first it's important to address that the Civil War did happen in the west, that Indian territory was involved. As I mentioned earlier, I didn't find out about native people and native participation in the Civil War until I was a undergraduate history major, a junior in a university. So I think that there are ways that when we teach the Civil War we can bring up that it's not only just in a north-south viewpoint or just between the Union and the Confederacy but that native people also were involved in a variety of ways.

For example, some native people just wanted to be left out of the sectional conflict, out of the conflict of the Civil War. It doesn't mean that they weren't aware of what's happening around them, that they weren't of the political and social battles going on but they wanted to be left alone and they wanted their sovereignty respected and preserved. But eventually, all five nations ally with the Confederacy. They did have some similar interest, slavery being one factor.

One thing that teachers, though, can emphasize is the point that we talked about including treaties and looking at treaty language. That will give students an idea of why some native nations participated in the Civil war or particularly sided with the Confederacy. Because for example, particular the Cherokee, the Choctaw, and the Chickasaw, they felt that the federal government did not respect treaty obligations. They did not respect annuity payments. And that was one of their main reasons for siding with Civil War. So slavery was a part of it, but ti wasn't the major part of it. So teachers involving treaties early on and considering tribal rights will help students to have a broader view of the Civil War and how it happened in Indian territory.

I think another way teachers can emphasize the importance of the Civil War among native people is to think about how it divided some nations. So for example, the Cherokee Nation in particular was divided over the Civil War. At first, they wanted to remain neutral and then eventually they split. And then you have what was called Southern Cherokees who sided with the Confederacy and then you had Cherokees who ended up siding with the Union. Slavery is even abolished in the Cherokee Nation in 1863 but it ends up completely diving the population. Some slaveholders even end up fleeing to Texas to refugee because of the war and because of the disruption in lives.

So I think it's really important to emphasize to students that the Civil War affected even Indian families, disrupted life, disrupted social relations, even pitted people, family member against family members. Usually that's something that we teach only happened, for example, in border states between people who sided with the Union or wanted to side with the Confederacy. But, these things are happening in Indian territory as well.

Meredith McCoy: I just want to emphasize a couple of things that you said. One is that depending on where native nations were located their view of the Civil War might've been radically different. So nations further west would've viewed this as a sectional conflict between parties of another nation and they just didn't want to be involved at all. And why would they? They were their own nations looking at a conflict within another nation. But for nations who were closer by, they were making really calculated decisions based on their previous experiences with the federal government. So just as you were saying, if the federal government had broken its promises to native nations over, and over, and over again, then why would they side with that government that had repeatedly failed to deliver on the promises it had made? And we see other examples, like the Lumbee Nation in North Carolina that ends up siding with the Union because of its experiences with the Home Guard in North Carolina.

So these decisions about who to ally with are very complicated and they're place-based depending on each nation's particular circumstances. The same can be said for the treaties that happen at the end of the war. Many teachers and students are familiar with the fact that the Union and the Confederacy had to come to an agreement at the end of the war that was a treaty. But they may not know that the federal government also entered into treaties with specific native nations as a way to conclude their role in the Civil War as well. Could you speak to the particular demands that the United States made of these native nations when the war was over?

Nakia Parker: Yes. This is something that always surprises the students that I teach as well, that since the federal government did not view native nations as a part of the Confederacy, just allied with the Confederacy, the 13th amendment did not apply to any enslaved people who resided in Indian territory. So in 1866, each of these five nations have to sign separate surrender treaties with the United States. What's even more fascinating is that although the Choctaw and Chickasaw were separate nations, the federal government makes them sign a joint treaty. Historian Barbara Krauthamer says that really this treaty is very unusual. Because unlike the agreements that were signed by the Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole, this treaty really merges black people citizenship, freed people citizenship rights with Choctaw and Chickasaw claims to tribal sovereignty.

So what do we mean by that? So when the nations, two nations sign this particular treaty, they had to abolish slavery. They had to secede over 4 millions acres of land to the United States in exchange for $300,000. So the government said, "Well, we'll hold this land in ... We'll hold this money in trust for you until you give the freed people in your respective nations all citizenship rights." The Choctaw and Chickasaw would not agree to this. They said that this was an assault on their sovereignty. And in fact, some leaders even said, "Why should we be expected or required to do more for our freed people than white people in the former Confederacy did for theirs?" Freed people in the South did not get land at all. So many native leaders were infuriated that the United States made these demands upon them. So really, again, we can see these overlapping oppression and really the entanglement of freed people's rights and citizenship rights with native sovereignty. Native nations were really between a rock and a hard place. Those who had allied with the Confederacy, for lack of a better term, their assault on their sovereignty was wrapped up with giving freed people citizenship rights and tribal rights.

Meredith McCoy: I'm Meredith McCoy, and you're listening to Teaching Hard History: American Slavery. We can see how native nations became entangled in the capitalist system of chattel slavery and how that's linked to the systemic removal of indigenous peoples from their homelands. To learn more about how native nations became caught up in this practice of enslavement and fought to extricate themselves from it, listen to episode two of this season, Indigenous Enslavement Part 1 with historian Christina Snyder. Once again, here's my conversation with Dr. Parker.

Since removal in the Civil War, the rights of freed people has long been controversial within the native nations that you work with in your research. Could you address how these different native nations thought about the tribal citizenship of the people their citizens had previously enslaved and how did approaches vary between the governments of different nations?

Nakia Parker: For the Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole, they did give full tribal citizenship rights to their freed people. And as I mentioned earlier, in 1863, the Cherokee abolished slavery, so in tandem with the Emancipation Proclamation. Now, eventually, a few decades after giving full tribal citizenship rights and the ... There's a battle between Cherokee freed people as well as Seminole freed people. They're disenrolled, and that battle lasts for decades. It's not until 2017 in the Cherokee Nation that freed people ... It's ruled by the Supreme Court that freed people need to be reenrolled and receive tribal rights.

The Choctaw and Chickasaw are a different story. They never give full citizenship rights to their freed people. The Choctaw give partial rights, some land, some voting privileges to freed people in 1885. The Chickasaw never do. And really, their defense of native sovereignty and their refusal to accept freed people as citizens reflects an unwillingness to let go of their enslaved labor force. So even after the Civil War, until the treaty of 1866, slavery is still legal. Teachers can look at the WPA narratives and share the experiences of enslaved people who say that they were still sold on the auction block after the Civil War had ended because they were in the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations and they were not considered legally free.

In addition, some freed people also talk about that they experienced the same kind of violence and trauma that freed people did in the American South. Generally, for example, when we teach America history after the Civil War and we talk about the reconstruction period, we usually focus on the violence and trauma that freed people had to experience in the South, lynchings, poll taxes, the Jim Crow laws. We even talk about freed people who experienced convict labor, another type of enslavement. But, similar circumstances existed in certain parts of Indian territory with the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations. There were black codes that were passed, what could be considered black codes, that said that a person without a work contract could be convicted of vagrancy and then sold into enslavement. Lynchings occurred.

So freed people were constantly facing difficult circumstances in these regions but they were still fighting for their rights. So freed people actively petitioned, both native politicians and the federal government, to honor their citizenship rights and to resolve what their status was since the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations would not give them rights. And when the federal government and native leaders wouldn't give them rights, then they fought for them on their own.

For example, one of the major points of contention for many freed people was that they wanted their children educated. So one good example that teachers could use as a point of comparison is looking at all the freed people schools in the South and also how freed people got money, raised money, found teachers to teach their children and to provide educational opportunities. That was one of the most important things to them. A good comparison would be looking at freed people in the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations. They did the same things. They raised money. They built school buildings. They obtained books. They asked missionary teachers to come and petition them to give their children an education.

So again, we can see it really expands our idea of how to teach reconstruction, too, that these same types of battles that are occurring in the South are also occurring in some points of Indian territory, too. We can't forget about that region when we talk about reconstruction and freed people's rights.

Meredith McCoy: This continues to be such a fraught issue in Indian country today, and it's a really important thing for teachers and students to approach carefully recognizing the diversity of perspective and opinions on this issue as it continues to develop. As Nakia mentioned, there was a Supreme Court case in 2017 that decided this issue for the Cherokee Nation. While that decision brought closure for a good number of people, it also raises a dangerous precedent in the world of the federal government's encroachment on to tribal sovereignty. So there are ways in which we have to understand competing needs and competing perspectives and allow our students to hold those things in tension.

Cherokee scholar Julia Coates has written about this issue and she talks about how, yes, there is certainly racism within the Cherokee Nation that influenced Cherokee people's unwillingness to include freedman as tribal citizens, but there is also a defense of tribal sovereignty, a recognition of clan systems and kinship that defines someone as being a Cherokee citizen, and in other words that there are factors that are more complicated than just phenotype and perception of race at hand in this issue. So I would encourage teachers who are thinking about teaching this issue of freed people's rights to dig in, to listen to the variety of perspectives, to expose students to the variety of perspectives, and to be really attentive to the ways in which human rights and sovereignty are both at play in this issue.

Nakia Parker: It's a shame that tribal sovereignty has to be at the expense of freed people's rights, because that's how it seems that it's framed, but I also feel like that's a part of what colonialism does, right? That's the issue that we have, that we have to respect all viewpoints. And whereas you have freed people who, yes, by virtue of their labor, by virtue of their enslavement, their descendants deserve certain rights, but it's also framed in we have to be realistic and see that the United States government did expect things from native nations that they did not expect from former members of the Confederacy. They just didn't. They didn't require them to do so. So that also has to be acknowledged, too.

Meredith McCoy: So Nakia, how does an understanding of native people's enslavement, both of other indigenous people and of African and African-descended people, help us to more fully understand US history? As we've talked about throughout this conversation, this is a history that is complicated and difficult to understand. And if I'm thinking back to my own experiences teaching eight grade US history, I had enough to chew on just getting out the basic facts that I knew were going to be on the end of grade test. So why then, if this is a story that is so complicated and one that's not going to show up in my students's multiple choice questions, why should I commit to teaching this history in my classroom?

Nakia Parker: I think it's hard history to talk about but it's necessary if we want to understand the whole of American history and in particular if we want to understand slavery, the expansion of slavery before the Civil War. So we have to understand it from a variety of angles. First of all, without Indian removal, there's no expansion of slavery in the Deep South. We also have to understand that that institution also moves westward because of Indian removal. It helps us get a broader idea of the Civil War. Instead of thinking of the Civil War in this north-south binary or even in a black-white binary, we also realize that it went westward geographically. It involved the diversity of people, of native groups who felt different ways about this conflict.

I also think that looking at participation in native slavery also shapes the way we think about what happened after the Civil War and reconstruction. Perhaps we can talk about things like freed people's rights, the rise of convict labor very differently if we include Indian territory. It expands our view of history, and it also helps us to really push back against some dominant narratives and some myths about American history. For example, we think of native people as disappearing from the record. I mean, we see 1830 Indian removal happened and then we don't mention America Indian history until late 19th century, Plains Indian Wars. But when we consider Indian territory in the 1830s and native people participating in chattel slavery, it really does expand our view. It makes us realize that native history is also included in US history and in southern history. You can't teach the history of the American South and of the domestic slave trade without also talking about native history and native participation as well.

Meredith McCoy: That was an awesome answer. Nakia, it has been wonderful having you on the show. I've learned so much from you, and I know that our listeners will really benefit from having gotten this chance to hear you talk about your research. So thank you for coming on the show today.

Nakia Parker: Oh, wonderful. Thank you for having me, and I thoroughly enjoyed our discussion. Stay healthy and safe, everyone.

Meredith McCoy: Nakia D. Parker is a historian at Michigan State University. Her current book project, Trails of Tears and Freedom: Black Life in Indian Slave Country, examines the forced migrations, kinship networks, labor practices, and resistance strategies of people of African and Afro-native descent enslaved in Choctaw and Chickasaw communities from 1830 through 1866. Teaching Hard History is a podcast from Teaching Tolerance, a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center, helping teachers and schools prepare their students to be active participants in a diverse democracy. Teaching Tolerance offers free resources to educators who work with children from kindergarten through high school. You can find these online at tolerance.org.

Most students leave high school without an accurate understanding of the role slavery played in the development of what is currently the United States or how its legacy still influences us today. This podcast is part of an effort to provide comprehensive tools for learning and teaching this critical topic. Teaching Tolerance provides free teaching materials that include over 100 texts, sample inquiries, and a detailed K-12 framework for teaching the history of American slavery. You can find these online at tolerance.org/hardhistory.

Thanks to Dr. Parker for sharing her insights with us. This podcast is produced by Shea Shackelford. Russell Gragg is our associate producer with additional support from Barrett Golding. Gabriel Smith provides content guidance, and Kate Shuster is our executive producer. Our theme song is Different Heroes by A Tribe Called Red, featuring Northern Voice who graciously let us use it for this series. Additional music is Chris De Brisky and Circus Marcus.

If what you heard today was helpful, please share it with your friends and colleagues. And then tell us what you thought. You can find us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. We always appreciate your feedback. I'm Dr. Meredith McCoy, assistant professor of American studies and history at Carleton College, and your host for Teaching Hard History: American Slavery.

Slave Codes, Liberty Suits and the Charter Generation

Episode 12, Season 2

The Americas were built on the lands, labor and lives of Indigenous peoples. Despite being erased from history textbooks after the so-called first Thanksgiving, Indigenous peoples did not disappear. Colonial settlers relied on the cooperation, exploitation and forced labor of their Native neighbors to survive and thrive in what became North America. Focusing on New England, historian Margaret Newell introduces us to the Charter Generation of systematically enslaved people across this continent.

Print this Page

Would you like to print the images on this page?

Earn professional development credit for this episode!

Fill out a short form featuring an episode-specific question to receive a certificate. Click here!

Please note that because Learning for Justice is not a credit-granting agency, we encourage you to check with your administration to determine if your participation will count toward continuing education requirements.

Subscribe for automatic downloads using:

Apple Podcasts | Google Music | Spotify | RSS | Help

Transcript

Margaret Newell: Caesar ran away from his master, a blacksmith named Samuel Richards in 1739, and presented himself at the home of the local Justice of the Peace, Joshua Hempstead. And Caesar said he was a free man, and no man's slave, because his mother, a woman named Betty, had been, he claimed, wrongfully enslaved and kept in slavery so that he had been born a free man.

Margaret Newell: She was probably a Pequot Indian, and as a young girl had been separated from her family, made a refugee during King Philip's War, and sold at auction in New London. But these refugees were not to be sold as slaves for life. Many people who acquired Indians through these auctions in Connecticut and Rhode Island held them as slaves for life, and then tried to lay claim to their offspring. So this is basically what had happened to Caesar.

Margaret Newell: And Hempstead heard this case and he sent it to a jury. His community in New London decided that Caesar had been inappropriately enslaved and ordered his freedom. So Caesar won a jury trial.

Meredith McCoy: Caesar’s story reminds me of the importance of grounding our teaching of hard history in individual people’s lived experiences. Thinking about individual people helps us to remain focused on their humanity and dignity, and it also helps students remain engaged with the broader stories we're trying to tell.

Meredith McCoy: With my American Studies students at Carleton College, we've been reading City of Inmates, Kelly Lytle Hernández's fantastic new book. City of Inmates traces the history of incarceration in Los Angeles through the lens of settler colonialism. It's a story that begins with the Tongva people and their mistreatment at the hands of Spanish colonists, who introduced prisons as a way to police Indigenous bodies in an attempt to remove Tongva people from their homelands. Reading Hernández’s book, the connection between unfree forms of labor like enslavement, debt peonage, and chain gangs becomes clear.

Meredith McCoy: In the midst of talking about prisons as a violent system used in an attempt to eliminate Tongva—and later Chinese, Mexican, and Black—people, Hernández also tells stories of resistance. She talks, for example, about Native prisoners' many strategies for escaping from jail, and provides examples of Black-Native solidarity against incarceration. These are the stories that my students found most impactful during our class discussions. Using specific stories to connect structures of oppression with individual resistance helped them make sense of the hard history Hernández is telling.

Meredith McCoy: By bringing out these stories, Hernández develops what she calls a "Rebel Archive." She writes, "Grappling with conquest and elimination is a daunting task. How can historical perspective be helpful if it overwhelms us with the enormity of the work ahead?" Hernández goes on to say that the Rebel Archive "shows us more than conquest and elimination at play." It shows "resilience, protest, and rebellion—as it tenaciously documents how the criminalized, policed, caged, deported and kin of the killed have always fought back. They jimmied open the cages of conquest and stole away. They nursed the incarcerated. They took the settlers to court. They passed plans of revolution. They sang love songs. They charged the US government with genocide. And they set the city on fire."

Meredith McCoy: The Rebel Archive Hernández documents provides a model for how we might approach teaching the hard history of enslavement in our own classrooms. Continuing to center specific stories of the resistance of enslaved people provides us an opportunity to focus on their resilience. And as we do, the stark contrast between a system meant to dehumanize and individuals like Caesar who refused to become objects becomes all the more clear.

Meredith McCoy: I’m Meredith McCoy, and this is Teaching Hard History: American Slavery, a special series from Teaching Tolerance—a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center. This podcast provides a detailed look at how to teach important aspects of the history of American slavery. In each episode we explore a different topic, walking you through historical concepts, raising questions for discussion, suggesting useful source material and offering practical classroom exercises.

Meredith McCoy: In our second season, we are expanding our focus to better support elementary school educators, to spend more time with teachers who are doing this work in the classroom, and to understand the often-hidden history of the enslavement of Indigenous people in what is currently the United States.

Meredith McCoy: Talking with students about slavery can be emotional and complex. This podcast is a resource for navigating those challenges, so teachers and students can develop a deeper understanding of the history and legacy of American slavery.

Meredith McCoy: In this episode, historian Margaret Newell examines the history of Indigenous enslavement in New England. In an interview with my co-host Hasan Kwame Jeffries, she tells us about the intimate cross-cultural relationships between English and other Europeans and the Indigenous peoples they were enslaving in their homes. We will look at important instances of resistance and resilience, as Native people used the settler legal system to secure their own freedom. And we will learn about some easy-to-access resources that you can use to teach these same stories in your classroom.

Meredith McCoy: I'm so glad you can join us.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: I am really excited to welcome to the podcast, Margaret Newell, my friend, my colleague here at the Ohio State University, softball player extraordinaire. So Margaret, your areas of expertise include colonial and revolutionary history, Native American history. And when we think about colonial New England, we conjure in our mind certain images, a certain narrative about relationships between English colonists and settlers and Indian people. What is that narrative, and what are some of the problems with that?

Margaret Newell: One of the really pernicious narratives is the eradication of Indians from history. The assumption that they're sort of there for the Pilgrims, but they just go away. They cease to exist. They're overwhelmed by European technology, by European disease, by European superiority, and they just sort of disappear. The Indians are, in fact, essential to the survival of the colonial project and to the success of the colonial projects. You know, both through the kinds of voluntary help they gave, and for the involuntary help through slavery. Slavery is another testimony to the continued presence of Native Americans throughout the colonial period and their importance in colonial society, even though it's a very negative and involuntary participation. It's a way to restore Native Americans more generally to the story.

Margaret Newell: Including Indians helps us understand the regional differences and the regionality of African slavery in the Americas. In other words, it's a way to move away from the plantation complex as the only site of slavery, to think about other sites of slavery like the household. And to think about how maybe it was different to be an enslaved person in New England than it was to be an enslaved person in Barbados than it was to be an enslaved person in Virginia. And how was that different? And to be an enslaved person in Quebec or New Orleans or Santa Fe. You know, what things made it different?

Margaret Newell: Most enslaved people before 1700 everywhere are enslaved Indians. By the 18th century, there's been a big increase in the number of enslaved Africans entering New England, which had been dominated by Native Americans before then. The system of slavery in English America had become extremely developed. You know, elaborate legal codes created within these colonial legislatures in other regions. And there's so much travel, there's so much trade, there's so much engagement that New England colonial leaders and would-be colonial slaveholders know what the law is in other places, and they want to see their system brought in conformity with the changes they've seen elsewhere. So by the 18th century, the American colonists of English descent had created a full-blown slave system: hereditary slavery, chattel slavery, dehumanizing laws. And, you know, the question in New England was whether those laws would end up applying there as well. So they applied some, not others. They really kind of parse the system and make some changes, but resist others, including making slavery hereditary. So it's partly the influence of this global slave trade, these shared practices, that are not just English by this period, that are also in Spanish America, French America as well, this consensus, slave-holding consensus.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: But there's an influence as well between Native populations in New England on English populations in New England. In other words, there's a cultural exchange that's going back by the time you get to 1739, century-plus. And a political exchange and allies, and I mean conflict. So is that influencing some of this decision-making as well?

Margaret Newell: So all through the first decades of colonization in New England, there are a lot of complicated relationships between English and Indians, but many of them are relationships of trade, of alliance, of mutual interests, of communication, of mutual aid in warfare, and of kind of daily interactions. People often think of Indians and colonists as being—you know, living in very separate zones. And maybe they come together on this thing called the frontier. But, you know, people were in and out of each other's homes all the time. The English settled as close to the Indians as they could. They farmed Indian fields. They dug up Indians' caches of corn and other goods, and that's how they survived the first couple of years in Plymouth. You know, the Indians help, the Indians trade. All these things are what made colonization possible. So there's proximity amongst these settlements from the start.

Margaret Newell: And there's lots of interactions. I have all sorts of examples of Indians wandering in and out of English houses and vice versa. You know, some scholars look at the rhetoric surrounding warfare between Europeans and Native Americans and see, you know, cultural dislike, demonization, othering of Native Americans. And I look at the record and I see something very different and much more complex. So I think in times of great tension, the English might use, you know, very extreme language in describing Native Americans, dehumanizing, demonizing language, but they use that language to describe the French in times of extreme warfare as well. You know, I agree with those historians that don't see race as the main way in which people understood and identified and thought about people of other races and ethnicities that they were encountering. Instead, I actually think that the English thought of the Indians as people like themselves, which makes their decision to enslave them to me all the more complicated and problematic and in need of explanation. These aren't people being brought to them as slaves already. These are people that they are actively enslaving and continued to do so through the whole colonial period, sometimes in very personal ways. You know, sometimes they're enslaving people that they know, that are neighbors, that they might have interacted with in other ways before they enslaved them. So, you know, this is a highly personal set of decisions involved in enslavement. But I don't think it has to do with viewing the Indians as the ultimate others by any means.