On March 6, 1975, Leonard Matlovich, a United States Air Force sergeant awarded the Purple Heart for service in Vietnam, handed his captain a letter that began:

“After some years of uncertainty, I have arrived at the conclusion that my sexual preferences are homosexual as opposed to heterosexual. I have also concluded that my sexual preferences will in no way interfere with my Air Force duties.”

Capt. Dennis Collins slumped in his chair and said, “What does this mean?”

“This means Brown v. Board of Education,” said Matlovich, referring to the landmark 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case that declared it unconstitutional for public schools to reject or segregate students on the basis of race.

Now, Matlovich argued, it was also unconstitutional for the U.S. military to reject service personnel on the basis of their sexual orientation, something they had done since World War II by issuing a dishonorable discharge to anyone thought to be gay or lesbian. His letter, which asserted that his sexual orientation was irrelevant to his extraordinary record of service, was a direct challenge to that policy.

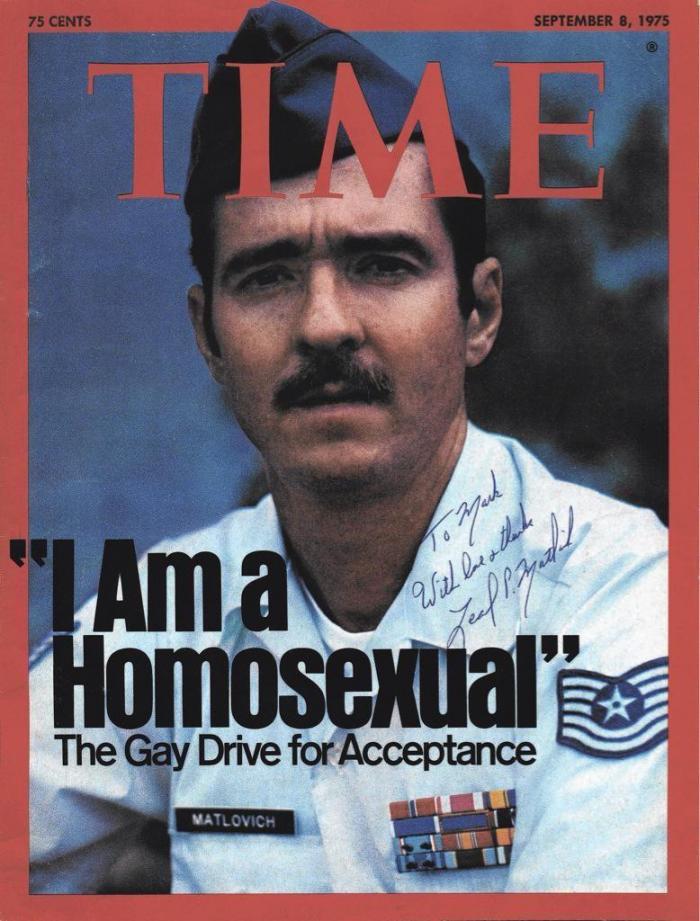

Six months later, Matlovich appeared on the cover of Time magazine, dressed in uniform, his medals clearly in view. The photograph was accompanied by four simple words: “I Am a Homosexual.”

Two months later, he was discharged. He filed an appeal with a federal district court judge. But the judge upheld his dismissal. Matlovich continued to appeal the case until, three years later, it reached the U.S. Court of Appeals, which ruled that his dismissal was illegal and ordered the federal district judge to reconsider the case. The judge took two years to issue his order: The Air Force had to reinstate him.

The Air Force vowed to fight the order all the way to the Supreme Court. Expecting to win but hoping to avoid the cost, they offered Matlovich a cash settlement of $160,000. Sorely in need of money five years after his dismissal, and fully aware of his poor odds at the nation’s highest court, Matlovich accepted, ending this particular battle but not the war.

Inspired by Matlovich’s pioneering action, numerous gay and lesbian service members continued to challenge the military’s ban against them, but with limited success. During the 1980s the military dismissed 17,000 gay and lesbian service members. Meanwhile, two internal Pentagon reports found that gays and lesbians posed no security risk, as had previously been alleged, and the public debate about the ban against gays in the military intensified.

In 1992, Col. Margarethe Cammermeyer was discharged after 26 years of exemplary service in the armed forces when she disclosed that she was a lesbian. Cammermeyer won a significant victory on behalf of gay and lesbian service personnel when in 1994, a federal district judge ruled that the military policy that had led to her dismissal was based on prejudice and unconstitutional. Other gay men and lesbians were winning similar lawsuits.

A year prior to the Cammermeyer judicial decision, the military replaced its ban on gays with a new policy. Entitled “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Don’t Pursue,” this policy declared that gays and lesbians could serve as long as they did not say anything to identify themselves as such.

But rather than improving life for gay and lesbian service personnel, the new policy made it worse. Discharges increased 92 percent in the first five years after the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy was invoked, according to the Servicemembers Legal Defense Network, which monitors the military’s treatment of gays and lesbians. Harassment, including death threats, verbal gay-bashing and physical assault, has also increased. In 1999, a fellow enlisted man beat Pvt. Barry Winchell to death with a baseball bat while he was sleeping because Winchell was gay.

The long battle by gay men and lesbians to serve their country without being forced to conceal a part of their identity continues today as they challenge the government’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy in the courts. Leonard Matlovich, who spurred on the struggle more than 25 years ago, died in 1988. But his words supporting the cause endure. His tombstone reads: “When I was in the military, they gave me a medal for killing two men, and a discharge for loving one.”