In American society, as in many others, religion shapes and informs everything from our language to our social habits. For us, one particular religion plays the hegemonic role: Christianity.

It is celebrated both in our calendars — where school breaks often coincide with Christmas and Easter, but rarely with the major holidays of other religions — and in our curricula, through "seasonal" art projects and activities like Easter egg drawings and "holiday" pageants.

Christianity is present in the turns of phrase from "turning the other cheek" and being a "good Samaritan," to being a "sacrificial lamb."

Taken together, these activities and experiences cause students who identify with Christianity to find their identity affirmed in school. Yet today, our classrooms include students from many religious backgrounds, and this "Christian normalcy" causes those who are not Christian to feel just the opposite.

My research into the life experiences of Hindu, Muslim and Sikh students of Indian American backgrounds uncovered the hidden cost of this "normalcy" in public schools.

Many students reported school experiences in which their religious identity was ignored, marginalized or actively discriminated against in a host of ways. The intense turmoil caused by these experiences threatened their ethnic identity development, their relationships with peers and family members, and their academic outcomes.

Their experiences offer insight and guidance for schools and educators.

Family Ties and Feelings of Exclusion

Classroom conversations about going to church, celebrating holidays or participating in Christian youth group activities produced extreme anxiety for students interviewed during my study.

For many Hindu, Muslim and Sikh students, religion is intrinsically tied to ethnic identity. Frequently their immigrant parents use religious activities and organizations as a way to gather with people like themselves and transmit culture to their children.

And yet, faced with Christian normalcy and feeling the normal childhood yearning to fit in with peers, many students were embarrassed to be associated with their own families and ethnic communities. Some avoided learning about their home religions.

"I remember at Christmastime having to lie about what my parents got me," said Priti, a Hindu student. Her parents "wouldn't get me too much, because they really didn't have the concept of" Christmas. Priti felt that describing the small gifts she received would emphasize her differentness from her Christian peers.

Priti also described how "on many occasions, when we would celebrate Christian holidays [in class], I definitely get the feeling that I was not a part of that celebration. ... There wasn't one solitary event, but a string of events for many years that made me feel that I was not part of this group."

Over time, this exclusion caused many students to feel self-conscious and even ashamed of coming from a faith tradition that was not perceived as "normal" by their teachers and classmates.

These feelings often had long-term ramifications — not only in diminished self-esteem, but also in the loss of knowledge about rituals and traditions, of aptitude with the home language, and even of connections with family.

Targets for Discrimination

But Christian normalcy, like religious dominance in many countries, is only one facet of religious oppression, which is not about theology so much as power. A religion becomes oppressive when its followers use it to subordinate the beliefs of others, to marginalize, exclude and deny privileges and access to people of other faiths.

The Indian Americans in my study shared stories of being targeted for discrimination and mockery because of their religions. One young Muslim reported that his homeroom teacher would often duck when he entered the classroom, saying, "You don't have a bomb in that backpack, do you?" The rest of the class had a good laugh, and this student felt compelled to laugh along throughout the school year.

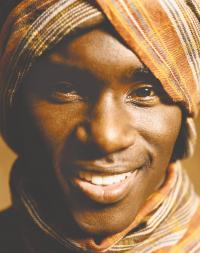

Harpreet, a male Sikh who wears a turban, recalled his high school's annual tradition of hosting a Christmas Dinner for the homeless, where students dressed up as different characters.

His teacher asked Harpreet to dress up as Jafar, the villain from the Disney film Aladdin, he said, "because I had a turban." The teacher treated Harpreet's turban as something cartoonish, ignoring its religious significance to Sikhs and conflating it with an Arab cultural emblem.

Other students were told they were "going to hell" or that they and their families needed to "be saved." When teachers overheard comments like these and did not intervene, many students took their silence as an endorsement of religious discrimination.

It's Academic

While many school districts make accommodations for students who are not Christian — for example, by excusing students for certain religious holidays — these accommodations can result in educational experiences that are unequal.

Consider the voice of a 13-year-old Hindu girl from Ohio:

"I hate skipping school to celebrate Diwali. After we celebrate, I still have to do all the in-class assignments and the homework for the next day. Now I tell my parents I'd rather just go to school."

"Making up" for religious observances is a burden Christian students do not carry. This reality can make it difficult for some non-Christian students to stay on equal footing with Christian peers, socially and academically.

For many Hindu, Muslim and Sikh students, religion is intrinsically tied to ethnic identity.

Another Hindu student, Nikhil, faced a different kind of academic challenge.

Since elementary school, Nikhil had experienced being teased for "praying to cows" and being "reincarnated from a dog." Like many Indian Americans, he developed the habit of keeping his home life separate from his school life.

When his public school's National Honor Society chapter decided to visit different churches to learn about religious diversity, Nikhil offered to share his religious life with his NHS peers.

"I told them that we should go to one of the Hindu services," Nikhil said, "and the NHS faculty sponsor said, 'No, we're not going to do that.'" When his offer was rejected, Nikhil decided he would stop attending Christian services with the honor society. As a result, he was dismissed from the NHS for "inadequate participation."

Nikhil feared academic retribution if he did anything about the expulsion. "[The NHS advisor] was also my English teacher," he said, "and I was afraid … it would reflect on my grade, so I never said anything."

When I interviewed him more than a decade later, Nikhil's voice still quivered with emotion as he recalled feeling "very, very mad. I was graduating in the top five of my class. Everybody around me had the honor stole on except for me – and the only reason was because I refused to go to church."

Making Religion Matter

As practitioners of multicultural education, we must recognize and respond to religion's importance as a cultural marker for many students, Christians and non-Christians alike. We must acknowledge and correct Christian normalcy in our classrooms and curricula. The answer is not to ignore or exclude Christianity; in fact, the opposite is true.

Consider these suggestions:

1. Know our own students.

There are a lot of religions in the world. Start with the ones present in your classroom.

2. Learn our ABCDs.

We don't need to be theologians, but we can at least learn the:

- Architecture: Know what the house of worship is called, like mandir (Hindu), masjid or mosque (Muslim), and gurdwara (Sikh).

- Books: Know the name(s) of the religion's holy text(s).

- Cities: Know the names and locations of the religion's holiest cities, like Amritsar (Sikhism), Mecca and Medina (Islam), and Varanasi/Benares (Hinduism).

- Days: Know the names and meanings of the religion's major holidays, like Diwali and Holi (Hinduism), Ramadan and Eid ul' Fitr (Islam), and Vaisaki (Sikhism).

3. Recognize religion as part of students' social identities.

Religion and religious institutions are one of the major ways ethnic communities – particularly immigrant communities – organize and gather. Understand how this makes religion especially salient for some students, and how the family's religion may be important even to students who don't see themselves as "religious."

4. Avoid the urge to "Christianize" religions and holidays.

Observe religious holidays in their own context and their own time, instead of lumping them all together in December. Don't assume holidays that fall close to a Christian holiday on the calendar share the same social or theological meaning. Likewise, don't diminish other religions by drawing analogies to Christian holidays – e.g., saying "Ramadan is like Lent" or "Janmastami is like Christmas."

5. Include religion in our curricula whenever it's appropriate.

Knowledge about religions is important for students living in our religiously pluralistic democracy, and in our global community. Religions influence the behavior of individuals and nations and have inspired some of the world's most beautiful art, architecture, literature, music and forms of government. When discussing these subjects, it's okay to acknowledge religion and its impact. Discuss how different religions deal with the concept at hand.

Understanding religious differences and the role of religion in the contemporary world — and in our students' lives — can alleviate prejudice and help all students grow into the thoughtful global citizens our world requires.