Everyone loves fairy tales—the easily identifiable villain, the flawless hero and, of course, the happily ever after. So it’s not surprising that teachers of the civil rights movement often skip the more confusing or distasteful aspects of that era, such as the dissension among black leaders and the racism that was widespread then, even among moderate white Southerners. Fairy tales have a place in our culture, but when history’s thorns are pruned until our past becomes just another story, we are doing a disservice to both our students and ourselves.

This school year we will mark the 50th anniversaries of many pivotal events in the civil rights movement. It would be easy to teach the familiar heroes and villains, but 1963 was messier than that. That year was a turning point in the movement—a period when civil rights leaders overcame differing viewpoints to conclude that small successes were no longer enough. If equal rights were to be attained, hard decisions had to be made—and acted upon.

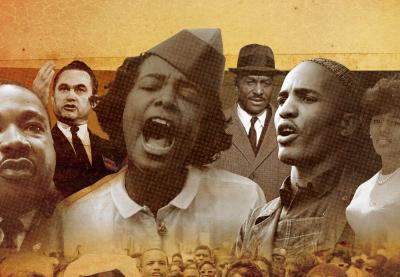

The cast of 1963 includes the figures students already expect to see on the stage: Martin Luther King Jr., President John F. Kennedy and T. Eugene (Bull) Connor, the public safety commissioner in Birmingham, Ala. But there were many others. What of Fred Shuttlesworth? Medgar Evers? Bayard Rustin? A. Philip Randolph?

When you plan your curriculum this school year, invite these and other lesser-known figures into your classroom. Students will engage more fully with the civil rights movement when it is presented in all its complexity.

January: Time for New Tactics

By the end of 1962, the stress of conducting small, simultaneous actions across the South had taken its toll on civil rights workers. Resources, both human and financial, were depleted, and there hadn’t been a major victory since the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-56. But when newly elected Gov. George Wallace of Alabama declared “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” in January 1963, it was clear to civil rights leaders that a change in strategy was needed.

April 3: Fred Shuttlesworth Invites Martin Luther King Jr. to Birmingham

Fred Shuttlesworth and other civil rights leaders made the strategic decision to consolidate their efforts in Birmingham, the most segregated city in the South. Shuttlesworth invited King to come from Atlanta and join them. Activists in Birmingham conducted daily mass demonstrations against white business owners and city officials who continued to enforce segregation. Many protesters, including King, were jailed.

King’s Letter From Birmingham Jail, written on April 16, 1963, will be marked on every civil rights anniversary calendar this school year. But unless students read it in context, they will not see it for what it was—won’t understand why King and others had come to believe that small, isolated victories would no longer suffice. The time for extreme action was at hand.

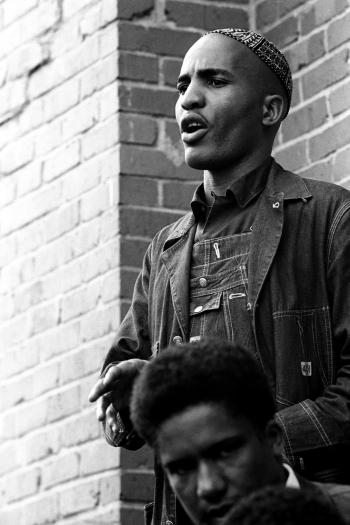

May 2: James Bevel Calls for a Children’s Crusade

Perhaps the most extreme action a society can take is to purposefully put its children at risk. This is what one of King’s aides, James Bevel, proposed: a children’s march that would pit young students trained in nonviolent protest against Bull Connor’s Birmingham police force.

The march began on May 2. Police confronted the young protesters, who were assaulted with fire hoses, attack dogs and tear gas. Steve Klein, communications director of the King Center, says that Connor “filled the jails with children.” Televised images of this brutality sparked international outrage.

Shocked by the violence, President Kennedy called for King to end the march. King agreed, but Bevel refused and pushed forward. Bevel’s tactics worked. In June, Kennedy proposed a comprehensive civil rights bill in order to avoid more brutality against the young protesters.

June 11: Vivian Malone and James Hood Enter the Schoolhouse Door

Every student knows that the schoolhouse door can loom large on the first day of classes. Imagine then, the fears facing Vivian Malone and James Hood as they sat in a car listening to Gov. Wallace’s threats to block them from entering the University of Alabama. Imagine the moment of decision when they stepped from the car to be escorted past Wallace at the doorway of the university’s Foster Auditorium. The students’ escorts were National Guard soldiers—the same soldiers who had stopped them from entering the campus just hours before.

Despite these obstacles, both students showed a great deal of courage as they walked in and paid their student fees. “I didn’t feel I should sneak in,” Malone said years later. “I didn’t feel I should go around the back door. If [Wallace] were standing in the door, I had every right in the world to face him and to go to school.”

June 12: Medgar Evers Killed by a White Supremacist

The civil rights movement did not spontaneously arise, full-blown. Activists had planned and nurtured it for a long time in their communities. Medgar Evers, for one, began tending the movement in Mound Bayou, Miss., as president of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL). He later became the first field secretary for the NAACP.

Bit by bit, Evers cultivated community resistance against inequity. He made bumper stickers, led protests and investigated vigilante violence, such as the murder of Emmett Till.

As Evers’ accomplishments grew, so did the determination of white supremacists to stop him. On the night of June 12, a member of the White Citizens’ Council shot Evers in the back as he walked from his car to his home. The murder took place just hours after President Kennedy had given a powerful speech supporting civil rights.

Evers’ death was but one violent act among many committed by segregationists who were set on stopping the movement. Community organizers acknowledged the danger, but continued to build the movement at the local level. In so doing, they ultimately overcame this violent opposition. Their individual courage made universal change possible.

August 28: Rustin and Randolph Realize Their March on Washington

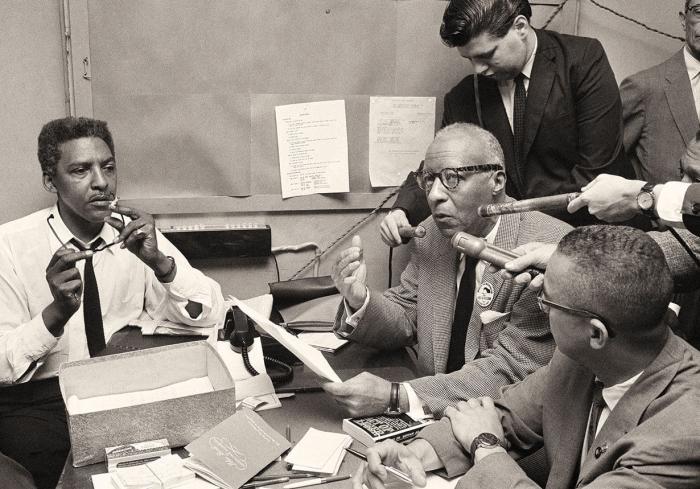

Civil rights leaders had faced racial bigotry all their lives. But they had not necessarily been subject to other types of intolerance, and intolerance can be harder to recognize when you’re not the target. Perhaps this accounts for some of their resistance to the activism of Bayard Rustin—an openly gay former member of the Communist Party.

In 1941, Rustin and A. Philip Randolph (an atheist and socialist) conceived the idea of a march on Washington to protest discrimination in the U.S. armed forces. President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued the Fair Employment Act to appease them and, as a result, the idea was shelved.

More than 20 years later, Rustin and Randolph’s plan for a march on Washington was revived. Civil rights leaders chose Rustin to be the chief detail man for organizing the march despite their fears that his homosexuality and political inclinations would be played up in the press by enemies of the movement. Those fears prompted the organizations involved to publicly ignore his contributions.

Rustin remained undaunted, throwing himself into his task. “The mood is one of anger and confidence of total victory,” Rustin wrote. “One can only hope that the white community will realize that the black community means what it says: freedom now.” A week after the march, Life magazine featured Rustin and Randolph on its cover as the organizers of the March on Washington.

None of these now-legendary events ended racial discrimination for good. “Happily ever after” isn’t for history books. What we can say, though, is that the individuals behind these events made choices—incredibly difficult choices—and the ones they made advanced the cause of civil rights in crucial ways.

We still fight segregation. We still struggle against racial discrimination. But we have made progress; we even have an African-American president. When we teach our students the civil rights movement in all its gritty detail, we show them that they don’t have to be Prince Charming to slay the dragon. We help them see that ordinary people can create extraordinary change.

Music in the Movement

When asked about the music of the movement, most people think of “We Shall Overcome.” But there were many other songs, such as “I’ve Been ’Buked, and I’ve Been Scorned,” performed by Mahalia Jackson during the March on Washington. Songs like this one gave voice to a passion that many in the South felt was not safe to express any other way.

I’ve been ’buked an’ I’ve been scorned

I’ve been ’buked an’ I’ve been scorned, children

I’ve been ’buked an’ I’ve been scorned

I’ve been talked about, sho’s you’re born

Dere is trouble all over dis world

Children, dere is trouble all over dis world

Ain’t gwine to lay my ’ligion down

Children, ain’t gwine to lay my ’ligion down

Discussion

Gospel music, and religion in general, played a key role in the civil rights movement. How do the lyrics of this traditional gospel song sung by Jackson at the march relate to the challenges faced by civil rights activists?