The disability rights movement’s foundational principle—“Nothing about us without us”—has been a rallying cry through much of the movement’s long narrative of intersecting with more high-profile social justice struggles. The legislation most people celebrate in association with disability rights, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, was influenced by the landmark civil rights legislation of 1964, and represents what people with disabilities had always sought: for their rights to be recognized and respected. But ableism doesn’t simply end with legislation; it remains a challenge, and the goals of equity and inclusion—in schools, society and the social justice movement—have yet to be fully realized.

Throughout much of the nation’s history, for the disability community, our existence was one of isolation and segregation. And while education is key to uplifting people, despite landmark decisions (Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954) and legislation (Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973), having a disability left many people on the margins of equitable education.

The unfortunate truth is that a barrier of ableism exists within the fight for justice. Even now, as intersectional struggles seek to be more inclusive, the disability community often must ask “the movement” to include us. So, what happened on the way to justice?

Where We Have Been—The “Crippled” Little Black Boy

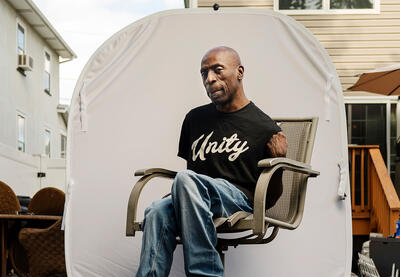

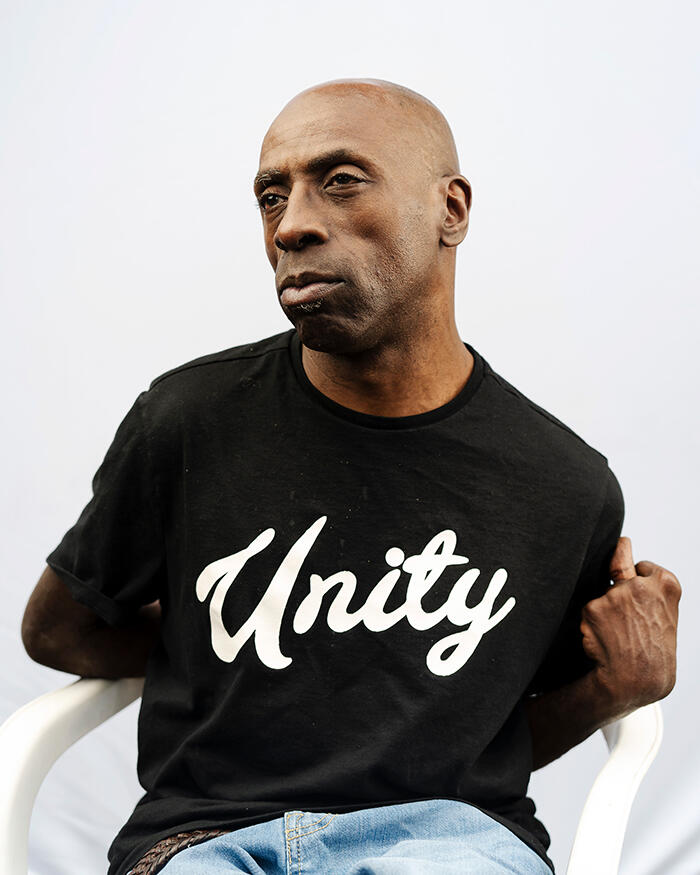

I began my school journey in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1975, which coincided with the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, later reauthorized as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in 1990. My arrival every day at the Elias Michael School for Crippled Children was a challenge. Being Black and a child with cerebral palsy, or “crippled” as I was called, neither I nor my classmates were expected to put forth any effort to learn. So, little effort was spent on teaching us. The simple act of requesting that actual math be taught got me sent to the principal’s office.

This was my earliest experience of the intersectionality of my identities not being fully considered, except in ways that created barriers. As a child, I was unaware to what extent racism and ableism were shaping my ability to be educated. It would seem these problems should have been addressed with the passage of the Handicapped Children Act and the Brown v. Board of Education decision. But the fact that I have race and disability at play is often overlooked, as though parts of my identity should be siloed when focusing on other parts. And the times all my identities are recognized, they compound one another in society’s biased view of both my race and disability.

Being overlooked plays in the back of my mind because my grandmother, mother and several family members were active in social justice and civil rights struggles. As a child, I spent a lot of time with my grandmother and had a unique front-row position to the women’s rights fight and the movement for civil rights coming out of the Jim Crow era. Later, in the 1980s and 1990s, family discussions addressed the possibility of the first Black president of the United States. And I listened intently, even though I didn’t fully understand what my parents were talking about as they spoke of things like affirmative action. Yet, beyond directly relating to me, disability wasn’t in the mix of those powerful topics about justice.

Then, as now, in conversations about criminal legal system reform, or about police interaction with Black and Brown youth, disability is rarely addressed. Or when it is, it’s a secondary effect. As someone who has had related experiences, the question lingered: “Why am I not fully included in these discussions?” That question was reinforced when I became active within the social justice and disability rights movements. As I worked with various organizations on issues ranging from sexual assault and survivors’ rights to criminal legal reform and voting rights, there seemed one glaring omission in each of these struggles—reconciling the multiplicities of an individual’s identities. Understanding that a person could be Latine/x, trans and disabled and in need of access to schools and voting, of how those intersecting identities needed to be included, was absent from conversations.

Where We Are in This Struggle

The social justice movement still has difficulty including various parts of the equity struggle, particularly disability representation. When the overturning of Roe v. Wade engendered an outcry, people with disabilities were sidelined in the conversation. This is echoed across not just rights and access to reproductive care but social justice in general. For example, with the unrelenting attacks on voting rights, accessibility to the polls, let alone the ballot, are rare focal points for voting rights organizations.

Disability rights advocate Justin Dart Jr. laid out the possibilities in 1987, when he testified in front of the Select Education Subcommittee that, “We have all the human, technological, economic and political resources necessary to effect a cultural revolution which will utilize the methods and products of science for the dignity and quality of human life. We stand at a historic crossroads. We are approaching foundational decisions about the future of rehabilitation and the fundamental rights of people with disabilities. Let us not seek scapegoats, let us seek solutions. We have no irredeemable enemies, only enemy attitudes.” More than three decades later, his words remain relevant—both the problem and potential are still present.

Ableism as an impediment to the disability community’s inclusion was laid bare with the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many Americans dismissed the needs of people with disabilities or failed to understand how callous statements about those with other medical conditions who were dying affects our community. A recent study by researchers at Syracuse University confirmed that COVID-19 was far deadlier for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Yet the pandemic’s increased health risks for students with disabilities is often given minimal consideration as politics have led some officials to refuse the implementation of safety protocols to reduce the spread of COVID-19. This particularly endangers students with disabilities and prevents them from safely accessing in-person education. The attitude of “getting back to normal” fails to recognize the increased risk for some people and that “normal” wasn’t always equitable or inclusive to begin with, not in schools, workplaces, or society in general.

In the three decades since the signing of the ADA, even with other significant legislative gains, disability rights advocates still struggle to break through in attempts to get organizations working in the social justice space to realize that we have a common struggle. We are here. Include us. And not as an extension of benevolence, but because we are part of this shared humanity. Social justice organizations, political parties and national advocacy groups have platforms in which the disability community has vested interests. Yet there is still at times a disconnect. To make that link to the expansiveness of our community, the movement on all sides must be more aware that the -isms are real—including ableism—and they often exist not just “out there” in society, but within shared social justice movements. And the disability community itself must confront its own -isms, whether that is internal ableism, racism, homophobia or any other bias.

Too often, when intersecting identities are recognized, it is in the context of how our identities compound inequities. And while that consideration is important, there needs to be recognition as well that inclusion in the movement itself, in finding the solutions and having a place at the table for those conversations, is essential. No one should have to silo aspects of their identity to support or be supported by the present social justice movement. Unfortunately, in organizing and advocating for larger justice issues, the disability community, regardless of their shared identities, has been marginalized within these larger movements. And within the disability rights struggle itself, intersecting identities have also been pushed to the corners.

Listening to the perspectives of those with lived experience is key to understanding that disability is not a problem to solve but part of the total human experience to embrace. ‘Nothing about us without us’ has real and consequential meaning.

The essential need to confront ableism in seeking justice has led the disability community to view our challenges through the lens of “disability justice,” a term coined from conversations between disabled queer women of color activists in 2005, including Patty Berne, co-founder and executive and artistic director of Sins Invalid. Disability justice centers on individuals at the intersections of disability, race, gender identity and socioeconomic status, who are often left out of the social justice movement. Understanding intersectionality—not just as part of the inequity problem but also as part of the equity solution—must be a core value in the quest for social justice, and in that quest, the need for visibility of intersectional identities and connected struggles is essential. With that foundational understanding and the desire to solve issues in the affirmative for our communities, we all can strive to work together.

Where We Can Go

What does it mean to have body autonomy, particularly for people with disabilities? What does it mean to have access to education and housing and health care? These issues in the broader struggle for a just and inclusive democracy have begun shifting to embrace the diverse tapestry of the human experience.

We must work across issues, understanding that expertise is not necessarily found only in the traditional spaces, and that perspectives within the disability community are valid. Pity is not the issue; the desire to live, breathe, eat and be included in our culture, in our neighborhoods, in our communities, in our states, and in our country, is. And this active representation is more significant now with the focus on pride in our diversity. There has been an increase in positive visibility through concerted efforts like #WeThe15, Disability Pride Month and the disability movement flag—these are all notes of progress to elevate disability as part of the diversity of human experience in the quest for social justice.

So how can we improve disability inclusion in social justice and overcome ableism? As our movement seeks anti-racist legal reform, access to economic sustainability and employment, quality education, reproductive rights and bodily autonomy, we must include people with disabilities—who cut across all intersecting demographics. And we must be intentional in that inclusion.

On an organizational level, we can learn from those with a history of inclusion—Sins Invalid, World Institute on Disability, American Association of People with Disabilities, Disability Visibility Project, POOR Magazine, and Krip-Hop Nation—to share how to engage and make employment and activism more accessible. We are at the stage where fighting this fight minus the disability community undermines the ability to advocate for these issues in their totality.

In education, a focus on inclusive spaces, high expectations for students with disabilities and training for all educators is essential. Listening to the perspectives of those with lived experience is key to understanding that disability is not a problem to solve but part of the total human experience to embrace. “Nothing about us without us” has real and consequential meaning.

We can’t have a truly equitable social justice movement without disability rights representation and visibility. And we can’t have inclusive schools without disability inclusive spaces and accommodations for learning.

We are each the totality of intersecting identities that are all valid. And the social justice movement is a totality of our multiple struggles that must all be valued as well. We can work together and thrive together in building a culture of diversity and inclusion—beginning with the movement for social justice.