In the Mott Haven neighborhood of New York City, a group of third graders visited a local Oaxacan restaurant, La Morada, as part of a program in which they explored the topic of immigration. It was 2019, and the students in the largely immigrant South Bronx neighborhood came from cultures disparaged by then-President Donald Trump and other politicians.

“We wanted to instill pride, and also talk about … who we are and what we contribute,” explained Myra Hernández, the program’s creator. “And, of course, one of [those contributions] was food,” she added. Two members of the family who owns La Morada, Marcos and Carolina Saavedra, told the students about their own journey from Mexico to the United States and “their connection to their food being a connection to their culture and their Indigenous identities.”

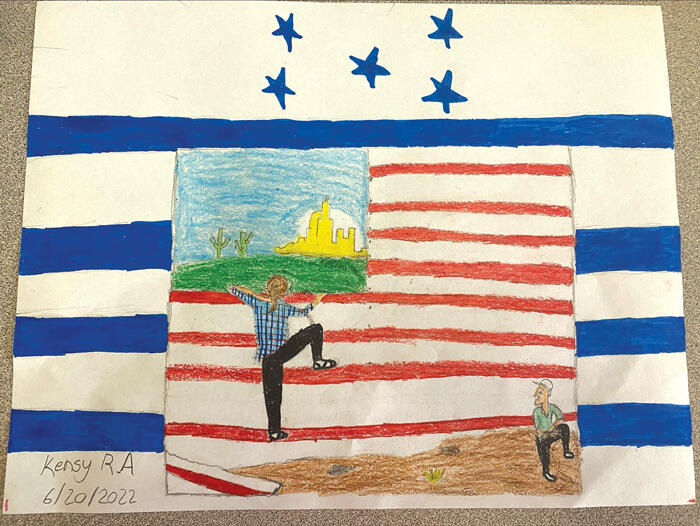

In San Antonio, Texas, a group of high school and middle school students recently visited the Centro de Artes for an exhibit of art by local immigrants. Afterward they created their own artworks and told their own stories. They told of being reunited with parents after many years and of fears of never seeing their grandparents again; they painted pictures about their hopes and dreams for life in the U.S. and the sacrifices they made to be here. The program was organized by the school district’s Dual Language, ESL and Migrant Department.

…while educators can take many concrete measures to lessen obstacles, community organizing can provide significant lessons about agency, resistance and power that students carry with them for a lifetime.

The La Morada and Centro de Artes outings are two of the countless initiatives by educators, schools, parents and communities to support immigrant students, and especially students who are undocumented or from mixed-status families. Conversations with educators and organizers in Texas, Louisiana and New York about how they help children and families overcome the challenges they face in the U.S.—inside and outside of school settings—found that while educators can take many concrete measures to lessen obstacles, community organizing can provide significant lessons about agency, resistance and power that students carry with them for a lifetime.

Legal Obligations of Schools and the Challenges Faced by Undocumented Students

The legal rights of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. are severely limited, as is the ability of people to legally immigrate to the U.S. But one bright spot for undocumented students is the 1982 Supreme Court decision Plyler v. Doe, which held that all children in the U.S. are entitled to a free public education regardless of immigration status. The ruling says that schools cannot discriminate in enrollment because of immigration or language status, and all students must have access to regular classes and special programs. In addition, Plyler requires schools to provide translation and interpretation services to families.

However, the rights that Plyler protects barely scratch the surface of the problems undocumented and mixed-status students encounter. From logistical obstacles to fears for their parents’ safety, these kids have a lot to worry about.

“I didn’t have a single person on my high school campus or my university one that could help me navigate systems as an undocumented person,” says Julia Sean, reflecting on both the loneliness and the barriers that status created. “When you are undocumented, it means you don’t have a social security number, so it cuts you off at the knees when you need to do things like apply for work or try to get a driver’s license or submit financial aid forms.” Sean is now an assistant principal who coaches the multilingual learners team at an Austin, Texas, charter school.

Viridiana Carrizales remembers being in seventh grade and overhearing school office staff asking visitors for a driver’s license, which was an immediate red flag and “an indication that school was not a safe space nor a welcoming space for people like me.” She warned her parents not to come to the school.

As the CEO of ImmSchools—an immigrant-led organization that partners with educators to ensure schools are safe and welcoming for undocumented students and families—Carrizales has heard countless stories like her own. She recalls a parent who was refused entrance to pick up her child at school and was asked not to park on the grounds because the school “saw her as a threat.” She explains, “This is trauma, every time you get put in a position where people dehumanize you and make you feel less than because you don’t have a document or an ID.”

Students are traumatized, too. Sean recalls, “During the Trump years, kids [were] asking me ‘Am I going to get deported? Are they coming for my family? Why doesn’t he like us? Why does he say that we’re dirty, that we’re uncultured, that we are like these uncivilized people? Why, why, why?’”

In these immigrant neighborhoods, one constant is clear: children are living in fear that their parents might not be there when they get home from school. Not surprisingly, numerous studies have documented the adverse effects on children of living with these realities, including academic, emotional and health impacts.

Implement Supportive Practices in Schools

Educators can’t fix everything for their immigrant students, but advocate groups like ImmSchools can ask teachers to “focus on what they can do and what they can control in their classrooms,” says Carrizales.

“Every educator has the obligation to serve every student, and our undocumented and mixed-status students are protected by law.” But many schools are unaware of their obligations, or unwilling to meet them, so bringing attention to the Plyler requirements is often the first step in lowering the barriers students face.

It’s crucial for immigrant students to be respected throughout the school, from the front office staff to the curriculum to cultural excursions like the La Morada and Centro de Artes trips. Another positive model is the San Antonio Dual Language, ESL and Migrant Department’s annual Dream Summit. They take high school students to visit a local university, tour the campus and take part in sessions on financial aid that explicitly include information on what’s available to undocumented students. The Dream Summit day also includes information about students’ legal rights in encounters with ICE.

Best practices call for an “asset-based approach” to teaching, where educators recognize and celebrate the unique experiences and knowledge every learner brings to the classroom. Many schools, for instance, are dropping the term “English language learner,” which erases the fact that such students are already fluent in one or more languages; terms like “emergent bilingual learner” or “multilingual learner” are preferred.

Parent Engagement in School and Beyond

Equally important are practices that make schools as safe as possible and welcoming to families. These include enrollment and visitor policies that don’t require identification that undocumented families don’t have—like a social security card or a driver’s license. Schools should also have a plan for what to do if ICE agents come to the school.

Engaging parents and caregivers is critical to student success and a building block for wider civic participation for both children and adults. In San Antonio, Kelly Manuel, director for content-based language instruction and ESL in the Dual Language, ESL and Migrant Department, and her colleagues organize “parent pláticas,” evenings when they invite parents to campus to talk with program staff and one another about their hopes for the children and the challenges they face. “This gets us to know our parents better,” says Manuel, “and also parents get to know one another, and that helps them build community so that they can rely on each other.” A WhatsApp group started with one cohort quickly turned into a networking tool, with parents asking and answering questions about finding housing, work and healthcare, among other things.

In New Orleans, Louisiana, Our Voice Nuestra Voz (OVNV) is organizing immigrant and Black parents to fight for their rights. “When immigrant parents are at a school board meeting, or at a charter school meeting, and their children are sitting beside them,” OVNV founder and Executive Director Mary Moran says, the kids see “the courage of standing up to a targeted power center and being able to say ‘actually no, here is my story, here is my testimony, here is what I know about this school and how it’s serving students.’ It’s so powerful for children.” Parents are modeling agency as well as courage, and that example helps their children grow into the next generation of fighters.

Community Organizing—Nurturing Leaders

In the South Bronx, La Morada’s longtime community involvement and its connection to local educators have provided potent tools both for addressing student and family needs and for helping students become active community members. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the restaurant has organized a mutual aid food program that combines donations from a variety of sources, La Morada’s cooking and scores of volunteers to deliver fresh meals to thousands of families every week.

Hernández lives in the neighborhood and is one of those volunteers. In her role as a program coordinator and curriculum specialist at Behind the Book, a program that supports young readers, she worked with the third-grade team at P.S. 43 to find a way to address food insecurity and hunger among students and families. Hernández designed a six-week program that combined a book—Lulu and the Hunger Monster—a (virtual) assembly of the whole third grade with the author, Erik Talkin, interviews of community leaders by the kids, and another (virtual) visit to La Morada. The third graders learned about food deserts, food insecurity and food justice. Immigrant rights activist Marco Saavedra taught the children about mutual aid and the restaurant’s program, and Talkin explained how federal and state governments don’t protect undocumented immigrants.

The idea was to build “understanding that hunger or food insecurity is no fault of folks in the community,” says Hernández, and to show the kids “what people in the community are doing to meet the needs of their community members.” At the end of the program, the third graders produced a digital pamphlet on food justice, with links to local resources and student reflections, which the school posted on its website.

In the absence of government help, “We take care of us,” Hernández says, using a popular movement slogan. “We wanted the kids not to be put in this impoverished light. We wanted them to feel empowered because there’s a lot of amazing power in this community.” By showing the students an example of effective local organizing and helping them begin to understand the structural causes of poverty, this program made them actors in their own community and not victims in an unjust system. “They now have the language and the tools and the know-how to hopefully speak up,” Hernández says.

All these efforts—from the enforcement of rights in schools to parent activism to community organizing—help immigrant students overcome barriers to their education. Ultimately, it takes political power to change the systems that create those barriers, from the local level all the way to the national. People like Moran are organizing to build that power. The vision of OVNV is to go beyond fighting for their rights within the education system to “push toward transformational education, liberatory education,” she says, “finding ways for our community to show up in all of its assets and knowledge and wisdom and the technologies we’ve built over civilizations to not just be seen as human, but to lead.”

Immigrant families face systemic obstacles and oppression not just in relation to education, but to their very existence in the U.S. Educators can play a crucial role in easing such obstacles with awareness and enforcement of Plyler rights. Equally important, educators can empower students, parents and caregivers through best practices such as an asset-based philosophy in the classroom, and policies that create a safe and welcoming space for families in the school community. Family engagement is a recognized factor in student success, but in the case of undocumented or mixed-status families, it is also a powerful means to encourage families, when faced with the denial of their rights, to claim their agency.

Marco Saavedra witnesses this in the high school students who volunteer in La Morada’s food program. “Mutual aid and organizing, and even art, it’s all about agency,” he says. And once the students recognize their agency to participate, he continues, they become “active, and not just reactive” drivers of civic engagement.

“[That recognition] unlocks your imagination,” Saavedra says. And that is the best education of all.

A Primer on Immigration Law

Legal immigration to the U.S. is unavailable for millions of people. The main routes for legal immigration are employment, which generally requires having a job already lined up, and family-based. Family members of U.S. citizens can legally immigrate, but because of annual quotas, the wait is often decades long. And people admitted as refugees, the last major legal route, must be screened by multiple international and U.S. agencies and demonstrate a “well-founded fear of persecution” based on a limited number of specific categories; the number of refugees admitted annually is capped.

It is also possible to become a lawful resident through asylum, which, while based on the same criteria as refugee status, is not capped. To obtain asylum, a person presents themselves at a port of entry and makes a request for asylum. People already in the U.S. can also apply for asylum if they do so within one year of their date of entry. While presenting oneself at the border is the legal way to request asylum, successive U.S. administrations have treated asylum seekers as criminals, processing their initial paperwork and detaining them rather than releasing them into the country as their claim is adjudicated.

The majority of the estimated 11 million people who’ve come to the U.S. without access to a legal route are now stuck in a permanent underclass. There is virtually no way to adjust their status and gain legal residency, and their undocumented status bars them from everything from legal employment to government benefits. It also means that an ICE agent could knock on their door or raid their workplace.

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, implemented by executive order in 2012 because Congress has been unable to pass immigration reform for decades, gave a reprieve to certain young undocumented people, but no path to citizenship. It is currently being challenged in court, so while DACA renewals continue, no new people are covered under the program.

Detention has become the primary tool of U.S. immigration enforcement over the last quarter century. The 1996 Illegal Immigrant Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act made more immigrants subject to mandatory detention and made all non-citizens vulnerable to detention and deportation. In 1994 the number of immigrants detained in the U.S. was approximately 7,000; in 2001, it was 19,000; in 2019, it was over 50,000.

The Remain in Mexico policy from 2018 required asylum seekers at the southern border to wait in Mexico while their cases were processed, effectively remanding them to dangerous camps and severely hampering their ability to pursue legal claims. Title 42, a U.S. public health code, was used to summarily—and illegally—expel migrants at the southern border and deny them the ability to apply for asylum at all. The Biden administration has sought to end both programs, but legal challenges have delayed policy changes.

Resources to Support Immigrant Students and Families

Protecting Immigrant Students’ Rights to a Public Education

This SPLC resource offers information educators, caregivers and advocates can use to ensure schools meet their legal responsibility to multilingual and immigrant students and families.

Supporting and Affirming Immigrant Students and Families

Join Learning for Justice, experts from ImmSchools and the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Immigrant Justice Project for a webinar on supporting immigrant students and families.

Serving ELL Students and Families

With sections centered on instruction, classroom culture, policies, and family and community engagement, this guide is packed with recommendations for educators and schools.

Articles from Learning for Justice

Help Ensure Immigrant Families Have What They Need

by Alison Yager

School as Sanctuary

by Cory Collins

This is Not a Drill

by Julia Delacroix and Coshandra Dillard

What’s a Sanctuary City Anyway?

by Learning for Justice Staff