Shatara McPherson is rewriting her cousin's life.

"When he grew up, he was bullied, and he's in and out of jail now," the outgoing 13-year-old said.

Shatara and 7th-grade classmate Devon Fowlkes were among 30,000 students in 10 cities nationwide who participated in the Comic Book Project in 2004-05, writing on the theme of "Leadership."

The pair crafted a plot about a bullying girl named Montay and a new boy at school named Dont'e who becomes her target. After a scuffle, another character suggests that Montay go to counseling. Montay and Dont'e -- the character based on Shatara's cousin -- become friends and head off to the movies together.

"We got to work with each other, make up our own story and write our own parts," Shatara said. They also were able to imagine -- and perhaps realize -- better endings to real-life stories.

The three-year-old Comic Book Project, founded and directed by Dr. Michael Bitz of Columbia University's Teachers' College in New York, aims primarily to promote literacy. It also gives children an empowering creative voice and the ability to use material from their own lives -- something that often interests them far more than prepared texts.

Participants conceive, write and illustrate their own stories. They address topics like teamwork, environmental issues, violence in schools and racial harmony, often casting themselves as the superheroes and heroines.

Student-created characters use super-human powers like telekinesis -- and human powers of courage, kindness and intelligence -- to stand up to bullies, organize social-justice campaigns and address interpersonal problems.

One comic book by Chicago youth includes these lines: "I am an African American woman who is tired of the things she has to put up with. ... I am an African American woman who has found herself, her power and her freedom."

'Community of Hope'

Our Mother of Sorrows has 225 students enrolled in pre-K through 8th grade. It's an imposing stone oasis next to a cemetery, a church and a neglected park in West Philadelphia. A mosaic in front of the church proclaims: "We Are a Community of Hope.''

Paulla Jones-Hawkins, the teacher who supervised Shatara and her classmates, used the Comic Book Project with small groups of 7th-graders in need of extra help with reading, writing and study skills. Most of Jones-Hawkins' students come from struggling families and need extra support to build an academic foundation that will enable them to survive and prosper in high school.

The project addressed several of Jones-Hawkins' goals for her students:

- How to stick with a long project from beginning to end;

- How to express themselves clearly with the written word; and

- How to resist peer pressure that sometimes devalues achievement in favor of destructive activity.

Jones-Hawkins was so enthused by the project that she had her 7th-grade group devote a half hour to it every day from October to April. She'll have all four grade levels participate this school year.

Other students in Jones-Hawkins' 7th-grade group wrote stories whose central characters were isolated by their bullying behavior, then eventually transformed themselves into cooperative classmates with help and guidance from their peers.

"It's a chance for them to show what they can do," Bitz said. It's also a chance for these students to show off -- and be celebrated.

Peacemakers and Leaders

The comic books offer a dynamic way to teach the elements of fiction, part of her required curriculum, Jones-Hawkins said.

Students begin the process by sketching within individual panels, thinking about sequence and drafting a preliminary storyline on a "manuscript starter" before transferring their ideas to a blank 10-page "canvas" of panels. There, they do the final coloring and print dialogue, using crayons and colored pencils.

Students understand concepts of character, setting, plot, symbolism, conflict, climax and dialogue better than they would if they tried to memorize them from a worksheet.

As a supplemental writing assignment, Jones-Hawkins asked students to summarize their messages in a mission statement to accompany the comic books.

"For those of you who are peacemakers or leaders, you can tell your teacher to talk to the bully," 7th-grader Antoine Coleman wrote. "You can ask the bully what is the matter. Leaders should keep violence out of your community and your school. (We) came up with this idea because we see lots of people pick on other kids."

Students also wrote reflectively about their experiences assembling the comic books -- a process that in its length and depth was by far the most sustained school project they had done. Most wrote about the interpersonal issues that came up between them and the partners Jones-Hawkins had assigned them.

Her approach is just one of dozens educators took in implementing the project. "It's flexible enough that districts have been adapting it to their own needs," Bitz said.

Originally designed for 4th- through 8th-graders, the program has spread from 1st to 12th grades. Teachers have elected to allocate time once a week or more often. Some students work on comic books alone, others in large groups. One group in Philadelphia made puppets based on their comic book characters and performed live.

In Cleveland, the district made the program available to any school that wanted to be involved. However, most students around the country participate in an after-school setting.

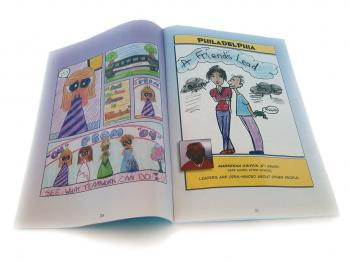

Among them was Markesha Griffin, a 5th-grader in the Safe Haven after-school program based at St. Matthew AME Church in Philadelphia whose story was selected to represent her city for the national anthology of 2004-05 work.

Markesha's main character, a girl named Brig, is pressured by popular kids -- football players, rockers and others -- to provide answers for a test. Meanwhile, a classic nerd named Morris, who doesn't need the test answers, is shown as isolated and bullied. "He was always alone," one comic panel states, with a later panel showing Morris being tripped in the hall. Brig helps him up and impulsively asks him to have lunch.

"With me?" Morris asks incredulously.

"I don't see anyone else in front of you,'' Brig says, winking. "Yes, you silly!"

The two become buddies. Brig, too, is ostracized but concludes by declaring she is "happier without fake friends."

A Commitment to Community

At a reception for the Philadelphia student-artists held at a public library branch in early June, Markesha, a tall 10-year-old whose ambition is to play professional basketball, beamed when her work was singled out.

"Leadership means to lead yourself into a better way of life," she said after receiving her certificate of recognition. She autographed copies of the anthology for other students.

A number of comic books were displayed on poster boards at the library, but in order to make every child feel included in some way, Bitz posts at least one panel from each comic book produced during the academic year on the project's Web site.

Bitz said the project plans to expand from 10 to 12 cities in 2005-06, adding Boston and Los Angeles. The new theme is "Community."

The exponential growth of the project, first tested in a single Queens, N.Y., after-school program in 2001, has been as much of an education for him as for the students.

"When we did the pilot, we said, 'Just do a book,'" Bitz said. "We learned it has to be a more structured process. At our training sessions, we ask, do you have the staffing? The space? Will you be committed?"

Jones-Hawkins is committed, as is her principal, Sister Owen Patricia.

Amera Pinkins, a 7th-grader at Our Mother of Sorrows, ran up to the principal waving a copy of The Comic Book Project's national anthology.

"Look what we did!" Amera exclaimed, breathless with excitement.

There, on the back cover, was a picture of Amera and classmate George Dudley holding a copy of their comic book. In a bit of serendipity, the character Amera modeled after herself -- puffy pigtails and all -- appears only a few inches from her smiling eyes.

Recalling the moment, the principal said: "This is monumental for our kids."