Some people find many reasons not to be openly gay.

Children's author James Howe knew he had 8 million reasons.

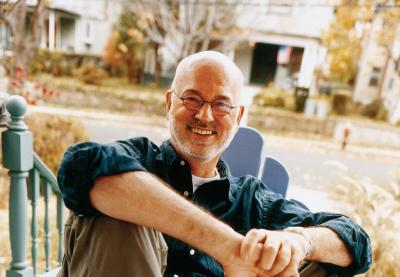

That's how many copies exist of his famed Bunnicula series. Nevertheless, eight years ago, at age 51, Howe risked steady sales and a stable career to become his full self.

As an "out" author, he's doing more. He's writing his beliefs -- beliefs of what could have been and what still can be.

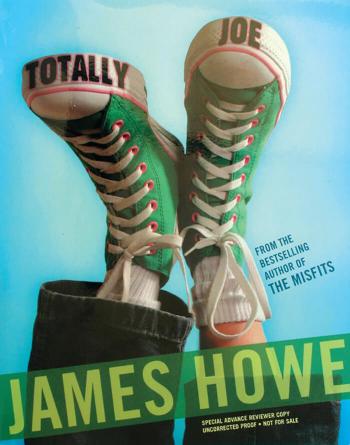

As a sequel to 2001's The Misfits, Howe's newest, Totally Joe, continues the tale of Joe Bunch, a charming, gay 7th-grader who faces a homophobic bully and other challenges before coming out.

Likewise, Howe's books face their challenges, something the author has noticed even more since the 2004 presidential election.

The Misfits, for example, was challenged in Iowa's Pleasant Valley School District in December 2004. Upset that a 6th-grade teacher was reading the book aloud in class, a parent protested the "indoctrination of children." If sexual orientation was taught in classrooms, so should the Ten Commandments, the parent claimed, presenting a petition with 186 names. The school board agreed, on a 4-3 vote, to ban teachers from reading this book aloud in elementary classes due to "age appropriate" concerns. The Misfits was allowed to remain in the school library.

Despite such challenges -- or maybe, in part, because of them -- the 59-year-old Howe is prepared to continue his literary mission of enlightenment by writing funny, captivating tales.

Howe spoke with Teaching Tolerance magazine, discussing his work, his life and the power of literature.

Before The Misfits and Totally Joe, had you ever written books with themes of tolerance and diversity?

Clearly, writers are drawn to themes that we write about, but we don't necessarily know what they are. It was a 4th-grade girl writing to me after Bunnicula was published, who for the first time gave me an idea of what my theme was.

In the book, a strange rabbit is suspected of being a vegetarian vampire after he comes into the home of, in my view, a typical suburban family. This girl wrote, "I learned from this book to be accepting of someone who's different. Harold just accepted Bunnicula. He said, 'He's different. So what?' Chester was suspicious of him and wanted to destroy him."

There it was. There was my theme. In my own mind, the book was a funny little exercise in writing. I hadn't thought about there being much substance to it.

In The Misfits and Totally Joe, an underlying theme that kept surfacing had to do with my own feelings of being different as a boy and then a man. My own shame about being gay, my own discomfort, my own wish that I could be open and accepting and be accepted. These feelings kept bubbling up in my work, which often celebrated difference and feeling good about who you are.

What did you risk as an author by coming out?

My history is so complicated. I know it can be very confusing to people. I've been married twice. So it's hard just to say, "I'm gay," and leave it at that. There's a story that goes with it. But I haven't experienced a (personal) backlash. I was somewhat concerned about it. My partner said to me, "Well, when Totally Joe comes out, you're out of the closet. Anyone who didn't know up to this point is going to know! Are you ready for that?" I think and hope I am.

And, more importantly, what did you gain by coming out?

I gained the ability to write from a deeper, more personal place in myself and in so doing to make a stronger, more honest connection to my readers. In Baby Be-Bop, one of my favorite young-adult novels, Francesca Lia Block writes, "Our stories can set us free ... when we set them free." In coming out, I set my stories -- and myself -- free. My hope is that my stories can now help others set their stories free.

Was The Misfits based on your childhood?

The Misfits came up at a particular moment in my life and the life of my daughter. My daughter was in the 7th grade and had been going through a very difficult time socially since the 4th grade. For whatever reasons, she was perceived as being different. By 7th grade, she was having a hard time, being picked on, being called names, being excluded. It was the kind of thing I experienced in middle school and high school. I was tired of hearing people say, "Kids will be kids. That's just part of socializing. It toughens them up."

The other piece was that, two years earlier, I had come out of the closet. I was finally able to say, "I am gay. This is who I am. This is a part of myself. It's not some shadowy, bad, dark shameful part of myself I have to cut off and hide any longer."

I said to myself, "I need to write a different reality for kids who are growing up gay." If I had grown up the way Joe is able to grow up in the world today -- or the way I hope one day kids who are gay, or are whatever they are, will be able to grow up -- I would have come to an understanding of who I was and been able to love myself and live free from fear, shame and self-hatred. That's where Joe came from.

In The Misfits, you introduce the theme of interracial dating with Addie and DuShawn. Did that spark any protest?

I've had no comment or reaction to the fact that a white girl and black boy were dating. What young readers have said is, "It's harder to believe that kids who are popular and not popular would date." I thought that was pretty interesting. That's one reason I got into that a bit in Totally Joe.

The other question that came up, a reason I wrote Totally Joe, is that kids thought Joe and Colin could never be boyfriends in the 7th grade. That would never happen. There's some truth in that. What I said to them was, "That's why I ended the book the way I did. I wanted you to ask the question, 'Why do I think this is so impossible?'" I want readers to be thinking about the assumptions they are making as I point the way to a different possible reality.

This dovetails completely with where I'm being attacked. "You want kids to think differently about homosexuality." Yes, I do. I also want them to think differently about popularity and racism and the assumptions they make about all kinds of things. I want them to think. I know that is heresy for some people. They do not want their kids to think on their own.

(In 2001) I started talking more in middle schools, specifically about The Misfits. Over and over again, the kids would zero in on Joe. "Why you'd write a kid like that?" Then they'd start to get antsy or giggle. I thought, "They really want to know, but they also are really uncomfortable. I need to write a book now that'll help them be more comfortable with this kid." This is the kid who is so often targeted. An effeminate boy is the one called "fag." He's the one pushed against the lockers. He's the one who is laughed at. He's the one assumed to be gay.

But I want kids to get to know him and like him. When I thought of the autobiographical form (as the narrative structure for Totally Joe), I thought, "This is the way to really let us know who this kid is, who he was as a little boy."

You visit middle schools?

I find them quite scary. (Laughs.)

Any time I'm invited to any middle school, it's because of The Misfits. From the moment it was published, it was embraced by schools. Even with the gay character being a part of it, that hasn't scared off many schools.

I try to say "yes" to as many middle schools as I can. I'm getting to come talk about something that really matters to me, to perhaps really make a difference. I always ask the administration how comfortable they are about my being open about being gay and talking about gay issues. I understand they may not be prepared for that, but certainly with The Misfits, it's a part of the book.

For the first national No Name-Calling Week, which took place in March 2004, there was a contest. I'd go to the winning school to meet students and speak. I was invited to Merrill Middle School in Des Moines, Iowa. I walked into this gymnasium. In filed 650 6th-, 7th- and 8th-graders. I was absolutely terrified. I had never spoken to so many middle-school kids at one time.

At the end of the speech, I got a standing ovation -- and it was started by the kids! I was blown away. This had never happened to me before with kids. The fact that it happened with middle-schoolers! I then met with small groups all day. I invited kids to write letters to me. Over and over, they talked about the fact that I had spoken their truth in the speech. That was an amazing experience and gave me a lot more courage to speak the truth when I go to schools.

In only one group did it come up that I was gay. I was asked a very pointed question. That has come up a number of times in other schools, sometimes in larger assemblies. Every time it does and I say that I'm gay, there is this huge moment that takes place where they suddenly get very quiet, or there's a little snickering. Kids might start rustling. I always use it as a teachable moment. "Let's talk about what's happening right now. Are you uncomfortable? Can't you believe I just said that? I'm here to tell you it's no big deal. It's who I am. Do we need to talk about it a little now? If we do, great. If not, we can move on." It's amazing how good that feels to me. And it's an important moment for them.

What are your thoughts on the case in Iowa's Pleasant Valley School District, when a complaint about The Misfits led to a ban on teachers reading the book aloud in elementary school while allowing it to remain in all school libraries?

That story began when a teacher was concerned about gay-related name-calling among students. She asked the librarian for a book to address the problem and found The Misfits. I was just so impressed and so floored by how that community fought -- and is still fighting -- against those few people who opposed the book. The students themselves protested and said their intelligence is being insulted and that they had every right to read the book. It's an ironic name (Pleasant Valley), but I don't see it as such a dark place. If anything, it seemed like a place fighting very hard to be enlightened.

In Totally Joe, the Life Lesson at the end of every chapter might tempt detractors to judge the book out of context. For instance, page 147 notes, "Religion is only as good as the people using it."

That chapter, even without the Life Lesson, may inflame a lot of people. Not that it's meant to. I'm certainly angry at what's being done in the name of religion against a lot of people, certainly against gay people. I feel we've become lazy about thinking in our country. I mean really thinking through issues and asking hard questions.

Unfortunately, teachers are being pushed to teach to the test, so they can't take the time to really deal with issues they may feel strongly about, issues they might want to teach in a particular way to help their students think for themselves.

That's part of what I want my books to do. I really want kids to think about the assumptions they make. That's why those Life Lessons are there, so Joe is forced to learn and grow. Joe grows through this book because he's put through the process of thinking things through and not making assumptions. In the end, he comes to understand that being gay and being gender-different aren't necessarily the same thing. He can't make assumptions about Colin, Zachary or even himself.

I'd like to think my books, what they're about, is opening the mind and the heart of the reader, to make the reader more open and compassionate, toward him- or herself and toward other people. I also want the reader to laugh. Laughing is so important in the process of opening the heart.