Few of today's teachers can remember an economic situation quite like the one we now face. To find analogies for the collapse of the housing bubble and the subsequent credit crisis, we have to search not our memories but our textbooks. The Great Gatsby and The Grapes of Wrath suddenly make more sense now. Generations of students have groaned at the task of memorizing acronyms like FDIC or FNMA: now they seem to leap off the pages of the history books. What will happen next? Will the economy bounce back, or will a wave of foreclosures create an invisible "Dust Bowl," uprooting hundreds of thousands of people? And how do we teach in this environment? To help our readers navigate these uncharted waters, we called in the experts. In the interviews below, social critic Meizhu Lui offers her take on where the crisis may lead us, and psychologist Melanie Killen talks about how to help your students cope in a time when the economic news is grim.

Meizhu Lui

Meizhu Lui was one of the people who saw a crisis coming. In her former role as director of the non-profit organization United for a Fair Economy, she warned about the crumbling of the American middle class, the predatory nature of subprime lending and the consequences of wealth inequity. Lui is co-author of the book The Color of Wealth: The Story Behind the U.S. Racial Wealth Divide, and director of the Insight Center for Community Economic Development's initiative to close the racial wealth gap.

What are the three biggest effects the economic crisis will have on children and families?

The first and perhaps most obvious thing is that families are going to be feeling a lot of economic instability. This translates to a lot of pressure on children, and that will translate into classroom behaviors.

For example, there was a fairly large layoff at IBM in Armonk, N.Y. The people who were laid off were, for the most part, upwardly-mobile, educated white suburbanites and IBM was considered a lifetime employer. After the layoffs, there was an increase in domestic abuse, drug use and alcoholism — and behavioral problems in children in school. Those are things we associate with the so-called "culture of poverty" that supposedly holds people back from prosperity, especially poor people of color. But there really isn't a "culture of poverty." When you're faced with economic uncertainty, it places you in a position of extreme stress — no matter what your class or race background is. And that anxiety is going to be apparent in the classroom, where more children will be manifesting the signs of a stressful home life. As this crisis unfolds, it's going to become increasingly clear to teachers that the "culture of poverty" isn't a valid idea.

The second major effect we're going to see is an increase in the number of students who move from home to home and school to school throughout the school year. This has always been a problem for children who live in extreme poverty. With the foreclosure and housing crisis, it's going to affect a new group of people who never imagined that they would be in this situation. We know very well that education is largely about the community. It's about the things parents and students can bring to the table. It's hard to build community when your students don't feel like they're going to be in one place for very long. This is a problem that could have an effect on the entire classroom, not just on the children who have lost their homes.

And rootlessness is just part of the picture. It's hard to learn when you're hungry or you have a toothache. As families begin to feel the effects of the economic downturn, you're going to see a growing number of kids whose families have become uninsured and can't go to the doctor. You're going to see students whose parents can't meet other basic needs. You're going to see that reflected in the academic performance of the kids who are affected by the loss of family income and assets.

Finally, communities of color are going to be hit harder than the white, middle-class community. Families of color are three times more likely to be steered into a subprime mortgage. Contrary to what you hear in some media accounts, these people were not choosing subprime mortgages because they did not qualify for other loans. There was a great deal of racial profiling going on.

For instance, Harvard did a study that looked at subprime lending in 2004 and again in 2007. They found that high-income African Americans were more likely to be directed toward subprime loans than low-income whites — and this was in liberal Boston.

What are the three biggest effects the economic crisis will have on schools?

First, because of the bailout of the banking industry, there will be less money for other federal expenditures — including the money that the federal government gives to state education departments and individual school systems. Property taxes are also declining, so local funding is also going to be on the decline. Finally, states will be limited in what they can do to fill the gap, since most states have bans on deficit spending. It seems almost inevitable that schools will be asked to operate with less money.

We all hope there won't be large-scale layoffs of teachers yet again, but teachers will certainly be feeling the squeeze. It seems that the one place the trickle-down theory truly works is in the realm of budget cuts.

Second, you can expect to see education played off, in the political sphere, against other needs, such as transportation infrastructure or energy. With other areas of the government facing the same funding issues, we're going to have to engage in a national conversation about our priorities. We need a major new investment in schools — we're having trouble competing with other countries already — but other interests will be seeking the same money.

Finally, you should watch the charter school movement, because we don't really know what is going to happen to (these schools). Because they receive public money, they could be affected by the decline in overall school funding. Most charter schools also rely on donations, and fundraising will be much harder for them in this environment. The charter school movement has been growing, but it's hard to imagine that this momentum will continue. More likely, we'll see some closings.

The economic situation is not likely to get better for the next few years, because there is more going on here than just a crash in the stock market. Manufacturing jobs have been going away, and wages have stagnated. Many people have shifted from full-time to part-time employment, and many good manufacturing jobs have been replaced with service sector jobs that don't offer the same benefits.

There's a lot of work to be done to get us back on track. So while teaching is more than a full time job, it will be essential to carve away a little time to get your voice heard on policy issues — not just on educational issues, but on what we can do to get our economy moving for ordinary people again.

Melanie Killen

Developmental psychologist Melanie Killen, Ph.D., is a professor of human development at the University of Maryland and associate director of the Center for Children, Relationships, and Culture as well as the principal investigator of the Social and Moral Development Laboratory, which examines how children, adolescents and young adults evaluate social and moral issues in everyday life.

How can educators support children during this time of economic upheaval?

First, educators need to give children information, educate them about what is happening, and do this in developmentally appropriate ways. This crisis is a teachable moment, one with historical, social and political lenses.

In elementary classrooms, educators can teach about the Great Depression as a way to understand what's happening now. With older students, teachers can go deeper into the complexities of that crisis and compare it to the one we're currently experiencing. Children can become frightened in times like these, and so regardless of age, we need to reassure students, let them know that we will get through this, as a nation, by working together, just as we did in the Depression era. The government is working very hard to resolve this crisis, and we can help, too, by caring for each other.

Second, educators need to prevent the stigmatization of children who are experiencing economic insecurity. For the first time in a long time, we're in an economic situation that will affect not only students from low-income families but also students from middle income and upper-income homes. For children already living at or below the poverty line, a tough situation will get tougher. Kids are going to experience a change in their social status, in their own eyes and in the eyes of others.

Today's schoolchildren grew up in a culture of consumerism. Over the last eight years, materialism dominated our culture, more so than in other decades. A lot of new things were being made, and the excitement of the technological advances too often translated into purchasing every new tech gadget — the latest and greatest iPod or iPhone, the latest video game (a product that takes you out of this world and places you in front of a screen), the big SUV, and the "cool" pair of $120 sneakers.

This crisis requires that we become less materialistic, that we turn toward a culture that centralizes inclusion, communalism and charity. We have to remember, as well, that children did not create this crisis. Adults created consumerism and they will have to work toward creating pragmatism and moderation in the area of consumables.

Schools increasingly will experience budget cuts. How does that reality create opportunities for educators and children to help shape a new "culture of communalism"?

It's very important that we are explicit. That's how you bring people together. People want to be part of the solution. They just need a structure that invites their participation. In St. Louis, when the Mississippi floods, for example, people of all ages show up to help sandbag the banks to prevent flooding into the streets of the city and into homes. It's the same sort of thing here: [we need to] generate ways for people to get involved. Adults in schools should communicate clearly: "These are tough times, and we're going to do everything we can. Here are some specific things we are going to do. And we need your help with the following solutions." If there aren't enough balls for young children to play Four Square anymore, invite students to create a new game that they can play with the resources that do exist. If it's homecoming or prom season then it could be effective to suggest clothes swaps to encourage a joint effort toward cutting costs for everyone.

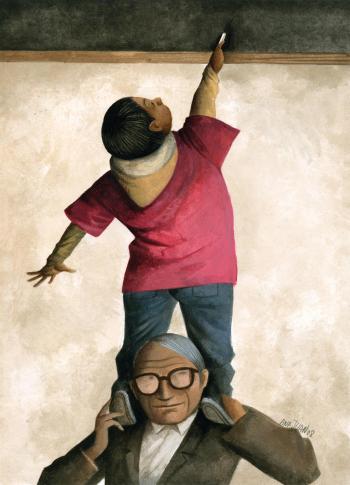

A lot of this depends on leadership. Teachers are leaders, and they are central to children's lives. We have an opportunity to show children how they can create positive change and live with hope. This is something that we witnessed during the presidential campaign, and harnessing this engagement through the current crisis is very important.

During this crisis, it's likely that more children will be more mobile, moving from place to place and from school to school. How can schools provide continuity for these children?

Student mobility can be tough for educators, and it will be particularly hard for those who have been teaching in more stable communities historically. For children, the situation has two dimensions — academic and social.

Again, children love to help when we give them a structure for it, and one of the best things a school can do is create a buddy system or a welcoming committee, pairing new students with children already in the school, to help new students feel part of the school community. Buddies or groups can help newcomers figure out where a class is in the curriculum, help with homework and also teach them the unwritten rules of the school, [including] small things like how kickball is played. Every school has its own variation of that game.

How can educators care for themselves during this time?

The best way to get through this is to be positive and pull together, to work closely with the school administrative hierarchy and get actively involved in budgetary decisions. In their personal lives, like everybody else, educators have to figure out how to get through it psychologically. Research is pretty clear that in situations like this, if you have hope, if you believe you can get through it, it's more likely to turn out that way. We have to be proactive, to believe that we can get through this - that the education system can get through this - and act on our beliefs in a positive and constructive manner to help make things better for everyone. It's an opportunity to grow as a community, and to involve children in the process of rebuilding as a culture.