Bria Justice was standing outside the Voting Rights Museum in Selma, Ala., when a woman she didn’t know grabbed her hand and led her to the back of the museum. Bria, 17, was a member of a student group visiting the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the site of Bloody Sunday on March 7, 1965, where armed police officers had attacked peaceful civil rights demonstrators.

“[The woman] stopped and showed me her mother’s footprint,” Bria said. “Her mother marched in the original march in 1965, and her footprint was up at the museum. It was her first time seeing the footprint, and she placed my hand on it and kept saying, ‘My mama was a foot soldier, my mama was a foot soldier.’ She asked me to never forget her mother. And I will never—I will never forget how strong she and her mother were.”

Bria said that moment changed her—“and it changed me in the way I want to change.” It also made her ask hard questions. “Why was I born into this life with very little prejudice against me? And why did others have to die for wanting equality?”

Experiences like Bria’s are what have inspired Jeff Steinberg to lead more than 7,000 students on 71 educational trips through the American South through his organization, Sojourn to the Past. Educational isn’t a strong enough word for such trips, says Steinberg. “These trips are transformational. It may not happen in 10 days, it may not happen in 10 months, but somewhere along the line, [students’] lives are going to be changed.”

A Personal Touch

The kind of person-to-person contact Bria encountered in Selma is essential for these trips, explains Lucas Schaefer, a seventh- and eighth-grade humanities teacher at The Girls’ School of Austin in Austin, Texas. Schaefer planned his own trip through the South, and at each stop, his group connected with someone who could speak directly with the students and put the civil rights movement in proper perspective.

“It’s easy to romanticize the period, to miss seeing the real sacrifices individual people had to make all along the way,” Schaefer said.

Steinberg of Sojourn to the Past emphasizes these same ideas on his trips, helping students connect themselves to social justice and nonviolent protest in the process.

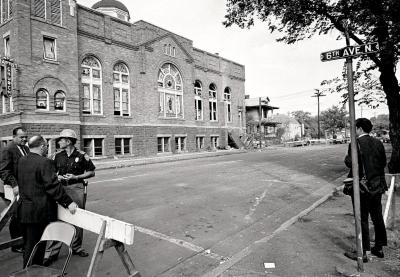

That’s why he chose Medgar Evers’ home in Jackson, Miss., as a regular stop on his trips. Students gather in the driveway, where Evers was assassinated, to discuss his work and death. Steinberg describes how Evers’ wife and children heard the shots and came running out to find their husband and father dying.

It’s at this point that Denise Everette, one of Sojourn to the Past’s regular chaperones, steps out from the crowd. And it is there, in that driveway, where students learn that Everette was born Reena Denise Evers, daughter of Medgar Evers.

Everette embodies the living legacy, courage and sacrifice of the civil rights movement. After she speaks, students sit in the driveway and write themselves letters, describing what courage and sacrifice mean and asking themselves how they’ll respond to injustice. Those letters are then collected and sent to the students six months later.

But Steinberg does not want students putting the movement’s activists on pedestals. “These trips are not about hero worship,” he said. “They’re about ordinary people doing extraordinary things, and about ordinary folks like you and me doing the right thing.”

Money Matters

Trips like the ones Steinberg and Schaefer lead are clearly valuable, but they come with a price tag. Steinberg’s trips run about $2,800—pricey even if a student wins one of Sojourn to the Past’s scholarships, which cover up to 60 percent of the cost. Other organizations plan trips that can cost as little as a few hundred dollars, but that still is out of reach for many students’ families.

Planning a Civil Rights Tour?

Jeff Steinberg of Sojourn to the Past recommends these three books as advance reading for civil rights trips through the American South:

• Free at Last: A History of the Civil Rights Movement and Those Who Died in the Struggle by Sara Bullard

• Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement by John Lewis with Michael D’Orso

• Elizabeth and Hazel: Two Women of Little Rock by David Margolick

How to address the cost-value conundrum? Marianne Magjuka, director of campus life at Wake Forest University, coordinates service-learning trips every year and encourages keeping costs as low as possible, offering scholarships and making fundraising a part of the preparatory activities.

Fundraising efforts can involve the community and support post-trip learning and reflection, but they also place a burden on students and the community—not to mention excluding students who can’t raise sufficient funds. The inequities highlighted when seeking funds for student travel were on Schaefer’s and his students’ minds when they returned to Austin following their tour of the South. They realized an element had been missing from their journey: an exploration of equity issues in their own city.

Don’t Forget Your Map

Teaching Tolerance’s Civil Rights Road Trip Map will lead the way to powerful experiences.

Sometimes it’s easy to overlook what’s close to home in favor of more distant destinations, but adopting a few simple strategies can make for fulfilling local adventures either around the block or just down the hall to the library. When students research (online, in the library and at any local historical museum) issues of equity and justice in their community, they begin to think more critically about details: Who’s telling the story? How might that person’s viewpoint sway how the story is being told? Local residents are a great resource as well. They can come to the classroom to tell their stories, or students can reach out to them in the community. Learning about the community also can lead to more in-depth service projects that address issues of equity and social justice—right in students’ backyards.

Mark Twain wrote, “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry and narrow-mindedness.” He had a point. Whether down the street or across the country, getting students out of their comfort zones and into new experiences can open their minds to social-justice issues in ways no textbook ever could.

Before, During and After Planning and Preparation

• Engage students, families and the wider community.

• Study and discuss pertinent history tied to the trip.

• Encourage students to journal or blog about their expectations for the trip.

On the Road

• Connect students to real people, not just monuments and museums.

• Allow time for discussion and reflection during the trip.

• Ask students to continue journaling as they travel.

• Allow students to feel uncomfortable—it’s part of the learning process.

Home Again

• Have students create presentations about the trip, describing the experience and how it affected them.

• Help students develop action plans outlining how they’ll change their behaviors because of the trip (for example, increased activism around a certain issue or speaking up against injustice in the moment).

Bring the voices of the civil rights movement into your classroom with these lesson plan ideas.