A subset of the Hard History project

What Learning About Slavery Can Teach Us About Ourselves

Print this Article

Would you like to print the images in this article?

This is an adapted excerpt from the first chapter of Understanding and Teaching American Slavery titled “Methods for Teaching Slavery to High School Students and College Undergraduates in the United States.”

Although there are problems in teaching slavery, there are bigger problems in not teaching slavery. Some teachers let their worries about teaching the subject deter them from giving slavery the attention it deserves. When they do, as the filmmaker Ken Burns notes, they participate in making “the great rift” between blacks and whites deeper and wider. Moreover, it’s bad history. Surely slavery, which caused and underlies this rift, was the most pervasive single issue in our past. Consider: contention about slavery forced the Whig Party to collapse; caused the main Protestant churches to separate, North and South; and prompted the Republican Party to form. Until the end of the nineteenth century, cotton—planted, cultivated, harvested, and ginned by slaves and then by ex-slaves—was by far our most important export. Our graceful antebellum homes, northern as well as southern, were mostly built by slaves or from profits derived from the slave and cotton trades. Slavery prompted secession; the resulting Civil War killed about as many Americans as died in all our other wars combined. Black-white relations were the main theme of Reconstruction after the Civil War; America’s failure to let African Americans have equal rights then led inexorably to the struggle for civil rights a century later.

Slavery also deeply influenced our popular culture. From the 1850s through the 1930s (except, perhaps, during the Civil War and Reconstruction), the dominant form of popular entertainment in America was minstrel shows, which derived in a perverse way from plantation slavery. Two novels have been by far our most popular—both by white women, both about slavery. Uncle Tom’s Cabin dominated the nineteenth century, Gone with the Wind the twentieth. During the nineteenth century, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was also by far our most popular play, with thousands of productions; during the twentieth, Gone with the Wind was by far our most popular movie (in constant dollars). The most popular television miniseries ever was Roots, the saga of an enslaved family; it changed our culture by setting off an explosion of interest in genealogy, ethnic backgrounds, and slavery. In music, slavery gave rise to spirituals and work songs, which in turn led to gospel music and the blues. Slavery influenced the adoption and some of the language of our Constitution. It affected our foreign policy, sometimes in ways that were contrary to our national interests.

Most important of all, slavery caused racism. In the United States, as a legal and social system, slavery ended between 1863 and 1865, depending upon where one lived. Unfortunately, racism, slavery’s handmaiden, did not. In turn, white supremacy, the ideology that slavery begot, caused the Democratic Party to label itself the “white man’s party” for almost a century, into the 1920s. Also during the 1920s, white supremacy led to the “science” of eugenics (human breeding), IQ and SAT testing, and restrictions on the immigration of “inferior races” from southern and eastern Europe as well as Asia and Africa.

Obviously, then, because of its impact throughout our past and in our present, we must teach about slavery. The question is how.

Relevance to the Present

The first step in introducing a unit on slavery is to help students see slavery’s relevance to the present. If not for slavery, people from Africa would not have been identified as a race in the first place, let alone stigmatized as an inferior race. Race as a social concept, along with the claim that the white race is superior to other groups, came about as a rationale for slavery. As Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas famously put it in 1968, racism is a vestige of “slavery unwilling to die.” This is terribly important for students to grasp, because otherwise many of them (and not just black students) imagine that racism is innate, at least among white folks.

As racism grew, owing to slavery, Europeans began to think of themselves as a group—“whites”—and classified others as “nonwhites.”

Slavery still influences how people think, where they live, how much money they have, and even who gets chosen to model in a catalog. Students should leave this discussion able to form useful ideas about slavery’s impact on our past and present in response to the question “Why must we learn about slavery?”

Slavery Led to Racism

The next step is to hold a conversation about racism. Many students of all races—in both high school and college—are unsophisticated as to what racism is and where it comes from. In the past few years, racism has come to be considered socially unacceptable, at least in interracial settings. That’s a welcome development, because it is both unfair to individuals and bad for our nation to treat people unfairly on the basis of their racial group membership.

Many Americans think people are “naturally” racist or that at least white people are. I have heard college professors, social scientists, and lawyers say that whites are racist by nature—that is, genetically. Nonsense. No one is born with the notion that the human race is subdivided by skin color, let alone that one group should be dominant over others. Racism is a product of history, particularly of the history of slavery. Racism was an historical invention.

Racism is thus neither innate nor inevitable. Students must never be allowed to say that it is without being contradicted—preferably by other students. Of course, showing how racism developed to rationalize slavery does not mean that whites adopted the idea consciously and hypocritically to defend the otherwise indefensible unfairness of slavery. Whites sincerely believed in racial differences. Indeed, between 1855 and 1865, white supremacy in turn prompted the white South to mount a fierce defense of slavery. During the Nadir of race relations—that terrible period from 1890 to about 1940, when the United States was more racist in its thinking than at any other point—whites used racism to justify the otherwise indefensible unfairness of removing blacks from citizenship.

Slavery was not always caught up with race. Europeans have enslaved each other for centuries. The word itself derives from “Slav,” the people most often enslaved by their neighbors before 1400 because they had not organized into nation-states and could not defend themselves adequately. Native Americans and Africans likewise enslaved their neighbors long before Europeans arrived. Ethnocentrism—the notion that our culture is better than theirs—has long existed among human groups. Perhaps all societies have been ethnocentric. Saying “we’re better than they” can rationalize enslaving “them.” But then the enslaved grow more like us, intermarry with us, have children, and speak our language. Now ethnocentrism can no longer rationalize enslaving them.

Although there are problems in teaching slavery, there are bigger problems in not teaching slavery.

One way to show the development of racism is through Shakespeare’s play Othello. Shakespeare wrote the play in 1604, but it derives from a story written down in 1565 by Giovanni Battista Giraldi but that probably dates back still further. Giraldi and Shakespeare considered Othello’s blackness exotic but not bad. European nations, beginning with Portugal in the middle of the 1400s, had already begun to enslave Africans. Eric Kimball explains in his essay in this volume that Europeans at this time stopped enslaving Slavs and instead picked on African villages, avoiding those Africans who had organized into nation-states or enlisting them as allies. Black slaves came to be seen as better than white slaves, who could more easily run away. By 1600 most slaves in Europe were black and most blacks in Europe were enslaved, so slavery began to be seen as racial. Since their color still identified them as slaves even after they had acculturated to “white” society, it seemed appropriate to keep Africans’ children enslaved.

Racism increased as this “new” slavery intensified. By 1700, white slave traders were carrying thousands of Africans every year to Brazil, the Caribbean, and the southern United States, where they and their children would work, unrecompensed, forever.

Historiography and Slavery

After clearing the air about race and racism, professors and teachers might continue their discussion of slavery in America by asking students to evaluate their textbook. What are the main things we need to know about slavery? Students can work in pairs to draw up the important questions. The teacher might seed some questions:

- How many slaves came to the British colonies and later the United States?

- From where?

- Where within the United States did they wind up? Why did slavery die out in the North but intensify in the South? (Be careful; other chapters in this book show it’s not as simple as “climate,” “crops,” or “topography.”)

- How did slavery affect US foreign policy?

- What were slaves' lives like? How did people respond to enslavement?

- Why were there fewer slave revolts in the United States than in Haiti, Jamaica, Brazil, and elsewhere in the Americas?

- Was slavery ending by 1860?

- How did the monetary value of slaves compare to other investments in the United States?

After generating an overall question list, students can examine their textbook to see how it measures up. If they feel it answers their questions, wonderful! Let them work together to uncover the answers. I suspect they will find that it doesn’t. In that case, teachers must help them to go beyond the textbook and learn more about slavery and its impact on their own.

Order the book

Teaching Tolerance readers get a special 30% off discount on Understanding and Teaching American Slavery! Just use this link and follow these steps:

1) Add the book to your shopping cart

2) Enter code UTAS

3) Click the “Update” button.

Offer expires December 31, 2017.

Print this Article

Would you like to print the images in this article?

Tongue-Tied

Print this Article

Would you like to print the images in this article?

Eight-year-old Rosetta Serrano didn’t know much about slavery when she entered the second grade at PS 372—The Children’s School—in Brooklyn, New York. But after studying slavery with her teacher, Steve Quester, she discovered something astounding: Black people had been enslaved by white people.

Every year, millions of students like Rosetta learn about the ugly and far-reaching institution that irrevocably shaped the history of our country. Teaching about slavery is tough. The facts are complex. The emotions those facts evoke are intense. It’s no wonder that educators tend to shy away from the topic, assigning readings from the textbook and avoiding class discussions.

Teaching about an institution as ugly as slavery will never be easy. But it can be done well, and the topic is too important to be left untaught.

Chauncey Spears, director of Advanced Learning and Gifted Programs in the Office of Curriculum and Instruction of the Mississippi Department of Education, says the key to teaching about slavery is taking a multi-faceted approach: “If enslavement is taught correctly and in the proper context—with a focus on real people making real choices—and there is a cohesive, collaborative teacher community with shared instructional values, there can be transformative teaching and learning that is responsive to students.”

Look Within

Creating the “proper context” Spears describes starts when educators look within themselves and acknowledge any personal biases or privileges that might influence their teaching.

Lisa Gilbert is an education coordinator at the Missouri History Museum. Confronting her own emotions about slavery has prepared her to have meaningful discussions about the topic with her students. “As an educator,” says Gilbert, “I want to be truly present with my students. For me, this means sharing my struggle with this history. I don’t understand how it could have been, and yet it was. It troubles me so deeply. And I don’t have the answers. But that’s OK, because history is something we wrestle with, something that challenges us to know ourselves and decide how we can use our lives to shape a better future.”

Set the Stage

Just as educators often feel uncomfortable talking about slavery, students may be hesitant to enter conversations or share their emotions about the topic. Developing a strong sense of trust allows for hard conversations and the asking of hard questions, says Spears.

Ina Pannell-Saint Surin, a fourth-grade teacher at PS 372, agrees. She works hard throughout the year to foster honest discussion about different cultures and guides the development of cultural literacy that enables students to appropriately phrase questions and seek answers.

It is within this construct that Pannell-Saint Surin is able to share her own emotional reactions to slavery. This, she explains, allows students to not only see the impact of slavery, but to share their own emotions.

“Sometimes,” says Gilbert, “we hide from the emotional content of this material. Sometimes we try to resolve it neatly, believing we will help students feel safer this way. But what we’re really doing is leaving them adrift to deal with whatever emotions come up, alone.”

Tell the Whole Story

It’s a goal Quester, the Brooklyn teacher, keeps in mind as he moves away from the traditional slavery story. Many textbooks focus on subjugation and tales of the Underground Railroad or the Emancipation Proclamation. But Quester deepens student understanding by broadening the narrative to show enslaved people as the courageous human beings they were.

Pannell-Saint Surin emphasizes culture when she teaches about slavery. “This way,” she explains, “we can impart the knowledge that Africans had rich, vibrant culture[s] that met their needs before being captured. And that [these cultures have] persevered through great odds and obstacles.”

That knowledge is a jumping-off point, says Gilbert, “the start of a conversation in which we ask: ‘Who do you want to be, and what role do you want to play in creating a more just society?’”

Don't

- Use role-plays. They can induce trauma and minimization, and are almost certain to provoke parental concerns.

- Focus only on brutality. Horrific things happened to enslaved people, but there are also stories of hope, survival and resistance.

- Separate children by race.

- Treat kids as modern-day proxies for enslaved people or owners of enslaved people.

- Make race-based assumptions about a child’s relationship to slavery.

Do

- Use primary sources and oral histories. Danny Gonzalez, museum curator for St. Louis County, Mo., recommends letters written by Spotswood Rice, a formerly enslaved man who enlisted in the Union Army during the Civil War.

- Underscore enslaved people’s contributions. Roads, towns, buildings and crops wouldn’t have been possible without them.

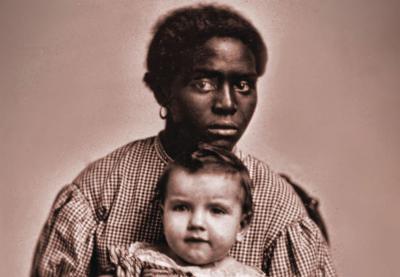

- Use photographs that reflect activism, family life and other daily activities.

- Choose texts that illustrate enslaved people as whole individuals. Try Henry’s Freedom Box by Ellen Levine or Minty: A Story of Young Harriet Tubman by Alan Schroeder.

- Organize field trips to historic sites that reflect enslaved people in a human and courageous light as well as to places that reflect the lives of black people beyond slavery.

- Introduce stories about black and white abolitionists. Black abolitionists were present, from the beginning, as vocal and courageous advocates for their people.

Essential Elements

Slavery in North America lasted for centuries, affected millions of lives, and contributed to every political, legal, social and economic institution fundamental to our country’s identity. Because the topic can be so overwhelming, the narrative of slavery taught in schools is often oversimplified: Owners of enslaved people become the bad guys; enslaved people become the victims; and Abraham Lincoln becomes the hero who saves the day.

The reality was much more complicated. While not a comprehensive list, the five dimensions of slavery listed below will help you approach teaching this difficult subject in more depth. These often-overlooked areas focus on the people involved, the choices they made, and the context within which they made those choices.

The Institution

The term slavery did not always hold the institutional meaning it did in colonial America and in European colonies. Enslaved people in ancient Greece, the Roman Empire and parts of Africa, for example, were closer to what we now think of as indentured servants or prisoners of war. The trans-Atlantic trade of enslaved people drastically redefined slavery in a number of ways.Enslaved people became the property of their owners for indefinite periods of time; ownership of enslaved people could be inherited; and the children of enslaved people automatically became the property of the family who owned their mothers. The perception of enslaved people as property that could be bought, sold, traded or inherited was marked by use of the term chattel slavery.

Slavery in European colonies also became racialized in a new way. There is evidence of Africans living and working in the American colonies as free men and indentured servants from the early 1500s. But once Virginia entered a period of rapid economic development, the British began importing enslaved Africans in massive numbers. There were no white enslaved people by the end of the 17th century, and being black automatically equated with being enslaved.

Economics

Like other European colonizers, the British relied on the forced, unpaid labor of Africans to create infrastructure and wealth where there had been only land. The tobacco, rice and—eventually—cotton plantations in the South supported developing industries in the North. This expanding economic reliance on the labor of enslaved people required the complicity of the nation. Similarly, the tightly bound “triangular trade”—cyclical importing and exporting of enslaved people, raw materials and manufactured goods among Africa, the Americas and Europe—was a system wholly dependent on forced labor.

The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 made this labor even more valuable, as producing cotton became faster and more efficient. The explosion of the cotton industry opened a new era of slavery in the United States, during which hundreds of thousands of people—mostly from the Carolinas and Virginia—were sold to plantation owners farther southwest. This so-called second middle passage, the second-largest forced migration in American history, tore apart innumerable families that had been stable for generations.

Maintaining these systems required more than just importing bodies and exporting goods. The rise of chattel slavery was accompanied by a widespread campaign of cruelty, degradation and cultural myth-making intended to dehumanize Africans. Historical accounts of auctions provide vivid illustrations of this dehumanization, as the process of buying enslaved people directly mirrored the process of buying animals. Enslaved people were bound with chains, physically examined, bid on and—in many cases—torn from their families, friends and communities.

What’s in a Word?

A lot. Referring to people as slaves implies that their entire being is wrapped up in their oppression. That’s far from the truth. Using the term enslaved person reduces the state of enslavement to an adjective—one of many that may describe an individual—and acknowledges that person’s full humanity.

Abolitionism vs. Anti-slavery—Do You Know the Difference?

Many anti-slavery advocates held racist views and wanted a white country. Abolitionists staked a claim to full humanity and true citizenship.

Culture

Despite slave owners’ attempts to strip enslaved people of their cultures, identities and relationships, Africans in the American Colonies and later the United States persisted in expressing elements of their myriad home cultures. Food, music, dance, storytelling and religion are all areas of life in which enslaved people blended their individual cultural memories (inherited or personal) with their experiences in the New World. Many of these cultural elements would go on to influence American society as a whole. From Southern cuisine and jazz music to call-and-response worship, the cultural contributions of enslaved people changed the cultural face of the United States.

Resistance

From slowing their work to breaking tools to eating food from the fields, enslaved people found subversive ways to exercise power and control their daily lives. Escape was a means to steal back freedom. As Frederick Douglass famously said, “I appear this evening as a thief and a robber. I stole this head, these limbs, this body from my master, and ran off with them.” There were also coordinated demonstrations of rebellion—such as assaults against plantation owners—and even organized, violent revolts. The 1739 Stono Rebellion and Nat Turner’s Revolt of 1831 were ultimately quelled; the Haitian Revolution succeeded. News of such revolts was terrifying to many American colonists, particularly in the South.

The American Revolution had brought hope to many enslaved people who heard, discussed and passed on the rhetoric of liberty and independence. Twenty thousand black loyalists took the risk of bartering loyalty to the king in exchange for promises of freedom, only to receive little support after the war was over. As the fight for American liberty was won, the system of slavery grew ever stronger.

Despite state laws forbidding the formal education of enslaved people, literacy spread within subsets of the community. Under threat of severe punishment, enslaved people actively built consciousness within both white and black populations about the horrors of slavery, the struggle for liberty, the abolitionist movement and organized resistance efforts. They often used liberation rhetoric that appealed to Christian beliefs.

Protections for Slavery

Slave codes enacted across the southern American colonies and states legally established the absolute power of those who owned enslaved people over their “property.” These codes defined consequences for—among other violations—violence against enslaved people (none), violence against owners of enslaved people (severe, usually death), educating enslaved people and traveling without permission.

Protections for the institution of slavery and states that sanctioned slavery were also written into the U.S. Constitution. The fugitive slave clause guaranteed owners the right to pursue and capture an enslaved person in any state or territory. In fact, a powerful Fugitive Slave Act was passed by Congress in 1850, partially in response to increased abolitionist activity.

Creating a Safe Space

Emotions aroused in students when discussing slavery will be no less intense than those experienced by educators, so it’s essential to create a safe classroom environment in which kids feel comfortable and supported in expressing their reactions to the material. An important part of creating that space is looking inward to identify your own biases.

Try these Teaching Tolerance resources to get started:

Print this Article

Would you like to print the images in this article?