Getting the Civil War Right

Print this Article

Would you like to print the images in this article?

William Faulkner famously wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” He would not be surprised to learn that Americans, 150 years after the Civil War began, are still getting it wrong.

During the last five years, I’ve asked several thousand teachers for the main reason the South seceded. They always come up with four alternatives: states’ rights, slavery, tariffs and taxes or the election of Lincoln.

When I ask them to vote, the results—and resulting discussions— convince me that no part of our history gets more mythologized than the Civil War, beginning with secession.

My informal polls show that 55 to 75 percent of teachers—regardless of region or race—cite states’ rights as the key reason southern states seceded. These conclusions are backed up by a 2011 Pew Research Center poll, which found that a wide plurality of Americans—48 percent— believe that states’ rights was the main cause of the Civil War. Fewer, 38 percent, attributed the war to slavery, while 9 percent said it was a mixture of both.

These results are alarming because they are essentially wrong. States’ rights was not the main cause of the Civil War—slavery was.

The issue is critically important for teachers to see clearly. Understanding why the Civil War began informs virtually all the attitudes about race that we wrestle with today. The distorted emphasis on states’ rights separates us from the role of slavery and allows us to deny the notions of white supremacy that fostered secession.

In short, this issue is a perfect example of what Faulkner meant when he said the past is not dead—it’s not even past.

The Lost Cause

Confederate sympathizers have long understood the importance of getting the Civil War wrong. In 1866, a year after the war ended, an ex-Confederate named Edward A. Pollard published the first pro-southern history, called The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates. Pollard’s book was followed by a torrent of similar propaganda. Soon, the term “Lost Cause” perfectly described the South’s collective memory of the war.

All these works promoting the Lost Cause consoled southern pride by echoing similar themes: The South’s leaders had been noble; the South was not out-fought but merely overwhelmed; Southerners were united in support of the Confederate cause; slavery was a benign institution overseen by benevolent masters.

A chief tenet of the Lost Cause was that secession had been forced on the South to protect states’ rights. This view spread in part because racism pervaded both North and South, and both ex-Confederates and ex-Unionists wanted to put the war behind them. Beginning with Mississippi’s new constitution in 1890, white southerners effectively removed African Americans from citizenship and enshrined their new status in Jim Crow laws. Northerners put the war behind them by turning their backs on blacks and letting Jim Crow happen.

From 1890 to about 1940, the Lost Cause version of events held sway across the United States. This worldview influenced popular culture, such as the racist 1915 movie The Birth of a Nation and Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 bestselling paean to the Old South, Gone With the Wind. As I point out in my book Lies My Teacher Told Me, history textbooks also bought into the myth and helped promote it nationwide.

What’s Wrong About States’ Rights?

But advocates of the Lost Cause— Confederates and later neo- Confederates—had a problem. The leaders of southern secession left voluminous records. The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s prompted historians and teachers to review those records and challenge the Lost Cause. One main point they came to was this: Confederate states seceded against states’ rights, not for them.

As states left the Union, they said why. On Christmas Eve of 1860, South Carolina, the first to go, adopted a “Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union.” It listed South Carolina’s grievances, including the exercise of northern states’ rights: “We assert that fourteen of the States have deliberately refused, for years past, to fulfill their constitutional obligations, and we refer to their own Statutes for the proof.” The phrase “constitutional obligations” sounds vague, but delegates went on to quote the part of the Constitution that concerned them— the Fugitive Slave Clause. They then noted “an increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the institution of slavery. ... In many of these States the fugitive is discharged from service or labor claimed ...”

South Carolina also attacked New York for no longer allowing temporary slavery. In the past, Charleston gentry who wanted to spend a cool August in the North could bring their cooks along. By 1860, New York made it clear that it was a free state and any slave brought there would become free. South Carolina was outraged. Delegates were further upset at a handful of northern states for letting African-American men vote. Voting was a state matter at the time, so this should have fallen under the purview of states’ rights. Nevertheless, southerners were outraged. In 1860, South Carolina pointed out that according to “the supreme law of the land, [blacks] are incapable of becoming citizens.” This was a reference to the 1857 Dred Scott decision by the southern- dominated U.S. Supreme Court.

Delegates also took offense that northern states have “denounced as sinful the institution of Slavery” and “permitted open establishment among them of [abolitionist] societies ...” In other words, northern and western states should not have the right to let people assemble and speak freely—not if what they say might threaten slavery.

Thoroughly Identified With Slavery

Other seceding states echoed South Carolina. “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery— the greatest material interest of the world,” proclaimed Mississippi. “... [A] blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization.” Northern abolitionists, Mississippi went on to complain, have “nullified the Fugitive Slave Law,” “broken every compact” and even “invested with the honors of martyrdom” John Brown—the radical abolitionist who tried to lead a slave uprising in Virginia in 1859.

Once the Confederacy formed, its leaders wrote a new constitution that protected the institution of slavery at the national level. As historian William C. Davis has said, this showed how little Confederates cared about states’ rights and how much they cared about slavery. “To the old Union they had said that the Federal power had no authority to interfere with slavery issues in a state,” he said. “To their new nation they would declare that the state had no power to interfere with a federal protection of slavery.”

Their founding documents show that the South seceded over slavery, not states’ rights. But the neo-Confederates are right in a sense. Slavery was not the only cause. The South also seceded over white supremacy, something in which most whites—North and South—sincerely believed. White southerners came to see the 4 million African Americans in their midst as a menace, going so far as to predict calamity, even race war, were slavery ever to end. This facet of Confederate ideology helps explain why many white southerners—even those who owned no slaves and had no prospects of owning any—mobilized so swiftly and effectively to protect their key institution.

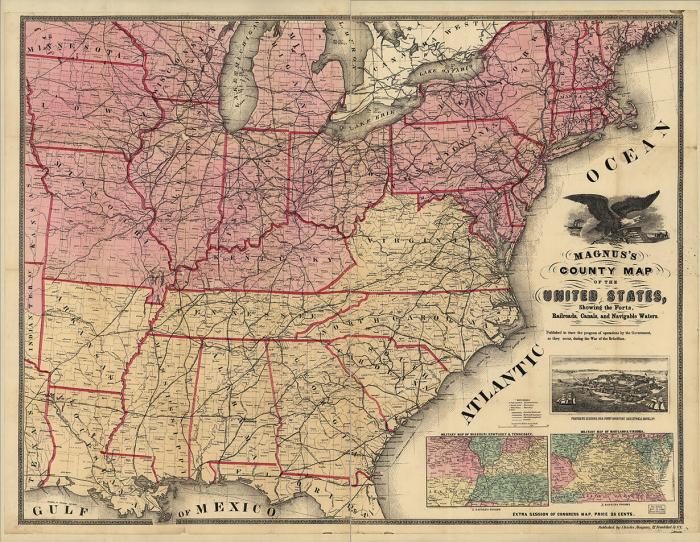

This historic map shows how the United States was divided in 1861, as the Civil War began. All of the seceding southern states were heavily dependant on slavery. Keeping African Americans in bondage allowed slave owners to cheaply grow cash crops like cotton, rice and sugar cane.

Tariffs, Taxes and Lincoln

The other alleged causes of the Civil War can be dispensed with fairly quickly. The argument that tariffs and taxes also caused secession is a part of the Lost Cause line favored by modern neo-Confederates. But this, too, is flatly wrong.

High tariffs had been the issue in the 1831 nullification controversy, but not in 1860. About tariffs and taxes, the “Declaration of the Immediate Causes” said nothing. Why would it? Tariffs had been steadily decreasing for a generation. The tariff of 1857, under which the nation was functioning, had been written by a Virginia slaveowner and was warmly approved of by southern members of Congress. Its rates were lower than at any other point in the century.

The election of Lincoln is a valid explanation for secession—not an underlying cause, but clearly the trigger. Many southern states referred to the “Black Republican Party,” to use Alabama’s term, that had “elected Abraham Lincoln to the office of President.” As “Black Republican” implies, Alabama was upset with Lincoln because he held “that the power of the Government should be so exercised that slavery in time, should be exterminated.” So it all comes back to slavery.

Confederate sympathizers have long understood the importance of getting the Civil War wrong.

Study the Writing of History

None of this was secret in the 1860s. The “anything but slavery” explanations gained traction only after the war, especially after 1890—at exactly the same time that Jim Crow laws became entrenched across the South. Thus when people wrote about secession influenced what they wrote.

And here the states’ rights argument opens a door for teachers to explain how perceptions of the past change from one generation to the next. Most students imagine history is something “to be learned,” so the whole idea of historiography—that who writes history, when and for what audience, affects how history is written— is new to them. They need to know it. Knowledge of historiography empowers students, helping them become critical readers and thinkers.

Concealing the role of white supremacy—on both sides of the conflict— makes it harder for students to see white supremacy today. After all, if southerners were not championing slavery but states’ rights, then that minimizes southern racism as a cause of the war. And it gives implicit support to the Lost Cause argument that slavery was a benevolent institution. Espousing states’ rights as the reason for secession whitewashes the Confederate cause into a “David versus Goliath” undertaking— the states against the mighty federal government.

States’ rights became a rallying cry for southerners fighting all federal guarantees of civil rights for African Americans. This was true both during Reconstruction and in the 1950s, when the modern civil rights movement gained strength. Today, the cause of states’ rights is still invoked against federal social programs and education initiatives that are often beneficial to people of color.

In other words, teaching the Civil War wrong cedes power to some of the most reactionary forces in the United States, letting them, rather than truth, dictate what we say in the classroom. Allowing bad history to stand literally makes the public stupid about the past—today.

Myths About the Civil War and Slavery

No. 1 The North went to war to end slavery.

The South definitely went to war to preserve slavery. But did the North go to war to end slavery?

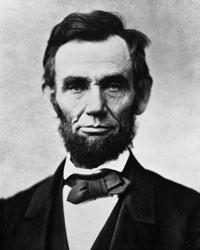

No. The North went to war initially to hold the nation together. Abolition came later. On Aug. 22, 1862, President Lincoln wrote a letter to Horace Greeley, abolitionist editor of the New York Tribune, that stated: “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that. What I do about slavery and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union.”

Lincoln’s own anti-slavery sentiment was widely known at the time, indeed, so widely known that it helped prompt the southern states to rebel. In the same letter, Lincoln wrote: “I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men every where could be free.”

Lincoln was concerned—rightly—that making the war about abolition would anger northern Unionists, many of whom cared little about African Americans. But by late 1862, it became clear that ending slavery in the rebelling states would help the war effort. The war itself started the emancipation process. Whenever U.S. forces drew near, African Americans flocked to their lines—to help the war effort, to make a living and, most of all, simply to be free. Some of Lincoln’s generals helped him see, early on, that sending them back into slavery merely helped the Confederate cause.

A month after issuing his letter to the New York Tribune, Lincoln combined official duty and private wish by announcing the Emancipation Proclamation, to take effect on January 1, 1863.

No. 2 Thousands of African Americans, both free and slave, fought for the Confederacy.

Neo-Confederates have been making this argument since about 1980, but the idea is completely false. One reason we know it’s false is that Confederate policy flatly did not let blacks become soldiers until March 1865.

White officers did bring slaves to the front, where they were pressed into service doing laundry and cooking. And some Confederate leaders tried to enlist African Americans. In January 1864, Confederate Gen. Patrick Cleburne proposed filling the ranks with black men. When Jefferson Davis heard the suggestion, he rejected the idea and ordered that the subject be dropped and never discussed again.

But the idea wouldn’t die. In the war’s closing weeks, Gen. Robert E. Lee was desperate for men. He asked the Confederate government to approve allowing enslaved men to serve in exchange for some form of post-war freedom. This time, the government gave in. But few blacks signed up, and soon the war was over.

No. 3 Slavery was on its way out anyway.

Slavery was hardly on its last legs in 1860. That year, the South produced almost 75 percent of all U.S. exports. Slaves were valued as being worth more than all the manufacturing companies and railroads in the nation. No elite class in history has ever given up such an immense interest voluntarily. True, several European colonies in the Caribbean had ended slavery, but that action was taken by the mother country, not by the elite planter class. To claim that U.S. slavery would have ended of its own accord is impossible to disprove but difficult to support. In 1860, slavery was growing more entrenched in the South. Unpaid labor made for big profits, and the southern elite was growing ever richer. Slavery’s return on investment essentially crowded out other economic development and left the South an agricultural society. Freeing slaves was becoming more and more difficult for owners, as state after state required them to transport freed slaves beyond the state boundaries. For the foreseeable future, slavery looked secure.

As we commemorate the sesquicentennial of that war, let us take pride this time— as we did not during the centennial—that secession on slavery’s behalf failed.

Print this Article

Would you like to print the images in this article?